Guest post: A portal to my past in the cloud forest

Searching for bears, I met a previous incarnation of myself

Take out or renew an annual subscription in April, and you’ll be entered into a prize draw to win a lovely box of goodies • There are a few spaces left for my in-person retreat in July

Hello,

When my friend Susy told me about a recent trip that she’d taken to a cloud forest in Ecuador, I was transfixed. Susy is Dr Susy Paisley, a conservation biologist, who studied spectacled bears in the Bolivian cloud forest. She has a PhD from the Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology, and is a winner of the Whitley Award for Conservation. She is also the founder of Newton Paisley, which creates beautiful fabrics and wallpapers featuring endangered species. And her account of her time in Los Cedros Biological Reserve wins my newly invented award for the best what-I-did-on-my-holidays story, which is why I asked her to write about it here.

I hope you enjoy it as much as I did, and do give Susy a follow on Substack to read more of her writing.

Take care,

Katherine

I am uneasy with the word ‘portal’. Maybe it’s okay in science fiction. Or in web admin. Yet I can’t seem to help myself. Nothing else seems adequately to describe a powerful experience I recently had: I definitely felt as if I passed through some kind of magic portal.

Once through, I stood, feet firmly planted, but head reeling, smack dab in the most impossible of places: my own past. As long as I didn’t catch sight of myself in a mirror, there I was, around 28 years old, a self I hadn’t been for at least as many years: cheeks flushed, body soaked, every sense and every muscle fully engaged, clambering around in a cloud forest, in impassioned pursuit of Andean bears.

And, somehow, there with me was a beamish 14 year-old boy, very tall, with the unmistakeable hazelnut-headed, brown-eyed look of my family. My own actual son?! Very accommodating of the portal to let him slip through with me.

I spent the latter half of the 1990s studying bears, culminating in my doctoral research in a site in Northern Bolivia of such remoteness and high elevation (my base camp was at 3700m), that a brief revisit of this sort has been out of the question. Anyway, that was the last millennium, for heaven’s sake. A time pre-cellphones. Pre-cellulite. You can’t just go back… I have a family now, a dog, chickens, guilt about my carbon footprint, petitions to sign, a business to run. I had never really even considered it a possibility.

But then, out of nowhere, a friend phoned with a proposal so perfectly crafted, so irresistible, that I soon found myself fully committed to a trip to the Ecuadorian cloud forest. Susan Turcot is an artist who used to live in the small English seaside town where our two sons were born, two weeks apart. The boys have been best friends all their lives, despite the fact that Susan and family moved to Montreal several years ago. Getting the boys together for this adventure held great appeal.

But that was only the beginning. I had heard about Los Cedros before. The reserve has legendary status in some conservation circles. It is famous for its astounding diversity, for sure - I mean the place has its own rain frog that changes from spiky to smooth and back again while you watch - but even more so as a sort of poster child for the Rights of Nature movement. In 2008, Ecuador became the first country to change its Constitution to assert that nature has the same rights as people. The new law remained untested until 11 years later, when José DeCoux, Los Cedros’ founder, used it to defend the reserve in court against a mining incursion. And won. In one move, the Ecuadorian Supreme Court’s verdict turned Rights of Nature from a constitutional idea into a powerful practical tool with global implications.

Subject, as so many of us are, to gnawing dread about the ongoing brutalisation of the natural world, The Rights of Nature movement offers a true source of hope. There is a great recent article about it in the Guardian. Guided by indigenous moral leadership, the unlikely marriage of dry jurisprudence with Loraxian idealism is creating something incredible: a robust reframing of humanity’s inter-connection with the natural world.

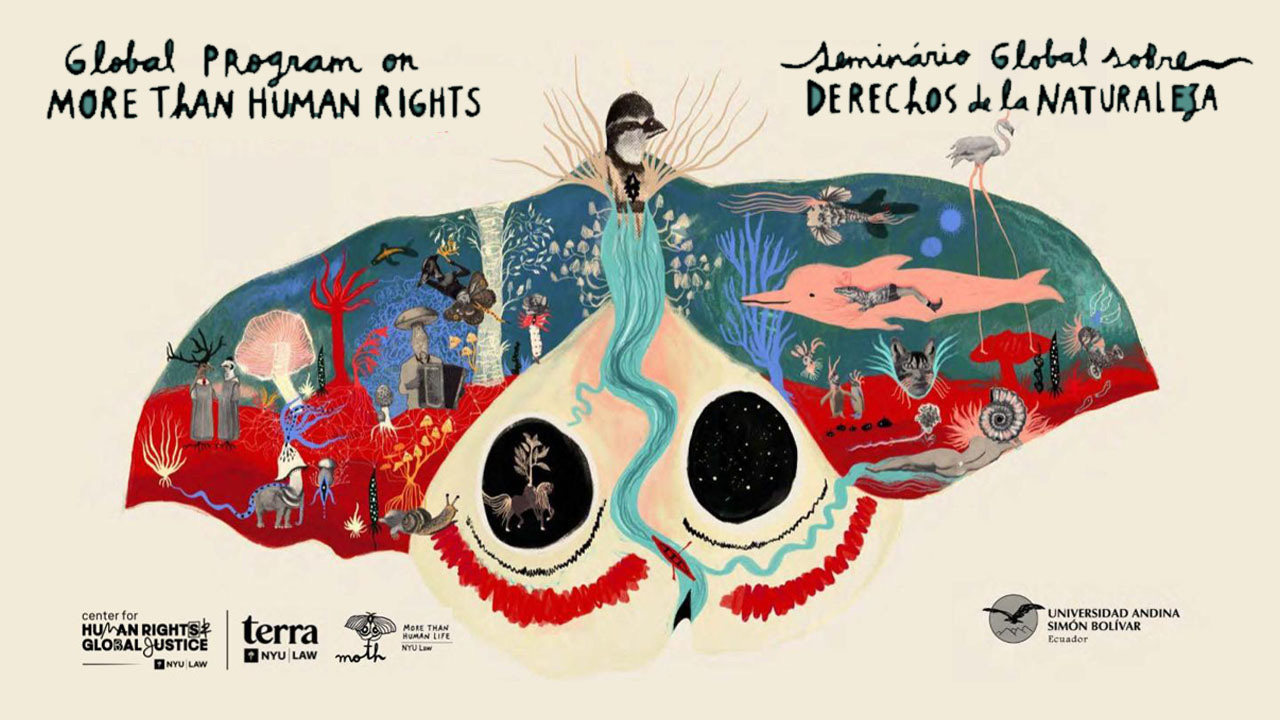

Susan knew I’d be equally intrigued by the artistic dimensions of Los Cedros. She told me about a 2023 expedition that included artists as well as scientists and lawyers which gave rise to the wildly boundary-pushing, trans-disciplinary MOTH (More Than Human) Rights Project, based at the NYU School of Law. She knew my musical son would love that Cosmo Sheldrake and Rob Macfarlane had been there and created a piece of music called ‘Song of the Cedars’ incorporating sounds of the forest. Frogs and birds feature, yes, but also more esoteric sounds like the slowed down echolocating frequencies of bats, and vibrations from the mycorrhizal networks of a newly discovered fungus. Add to this a truly novel legal bid to have the forest recognised as the song’s co-creator… Suffice it to say, I was beguiled.

•

In fact it was in Ecuador all those years ago that I originally learned from some locals about a famously shy species of bear, the Andean or spectacled bear, Tremarctos ornatus. Virtually nothing was known about its biology other than some basic observations of diet through faecal analysis. While basics such as home range and overlap and activity patterns were entirely unknown, colourful myths abounded, often about bears absconding with humans for escapades that would make the modern-day furries blush. I lost no time in setting out from the adobe hut where I was staying, and heading up into the elfin cloud forest of the Podocarpus National Park.

It was a strange experience, like becoming a giant, because the height of the tree canopy lowers imperceptibly as you climb until you emerge onto the high Andean grassland. In a moment that swerved the course of my life, surmounting a peak in the trail, I had an encounter with a bear, drinking from a pool of water, at a distance of only about 20 metres. Fur like a forcefield, like iron filings bristling from a magnet, it almost glowed with blackness. It had pale partial rings around the eyes. I didn’t breathe, blinking away my disbelief, in my little round spectacles. We looked at each other.

I think I imagined that I was always going to have that kind of luck with bears. This proved not to be the case, but it was a useful delusion and I was hooked.

At that time Ecuador was the most peaceful of countries but, sadly, in the past few years that has changed. Sandwiched between the volatile narco-states of Peru and Colombia, there are regions of Ecuador that are now plagued by gang violence. Though Los Cedros is not in one of these regions, the impact of news reports and national travel advisories has been devastating for international tourism. It took effort to convince our families that we’d be safe but we absolutely were.

The journey was easy. We arrived into the fancy new airport in Quito, were met by a taxi, taken to a cheery hotel and were collected the following morning. Los Cedros has its own driver whose first name, most perfectly, is Darwin. He threw our stuff into his truck and, after a few short hours’ drive through hulking landscape, our bags were being lashed to mules and we were beginning our ascent to the research station. Go if you can. They really need the support.

My metaphorical portal was more of a staircase, very steep and muddy, that takes about an hour and a half of uphill hiking to pass through. It is the rainy season, so you have to wear wellies and do a lot of comedic squelching. Lifting your eyes from the muddy, rooty ground, you begin to comprehend that you have arrived in a wonderland. A truly hyper-diverse wonderland - ornamented on every surface with dripping, gleaming, infinitely variable life. An astounding 300+ tree species per hectare soaring up through multiple levels of understory; 400+ species of birds including bombastic cocks-of-the-rock and quetzals, which are truly the most extravagantly glamorous beauties. Strangler figs like cages from some dark fairy-tale. Whole universes of life: fungi, orchids, bromeliads, lichens, mosses, lianas. Strange massive fruits and a porcupine skull casually strewn about on your path, endangered Ecuadorian Mantled Howler monkeys booming in the distance.

I don’t want to give you the impression that this portal sent me back to a specific time or place. The trick was that I suddenly felt like I used to feel - like a previous incarnation of myself that I thought was extinct. Twenty-two years ago, pregnant with my first child, I thought in a matter-of-fact sort of way, that I, the self I had been until then, was scheduled for the chop. With any luck, I would emerge a new person, a type of creature called a “mother”, who might well be capable of happiness, but would have none of my previously treasured freedom or sense of invulnerability. Part of it was that my adult life up to this point had transpired in wild places in Latin America, and motherhood had me settling in England. But it felt more fundamental than that. A change in state of matter. A metamorphosis - like a caterpillar going into a cocoon, all tissues and organs dissolving completely, molecules recombining, and an entirely new creature emerging. Like a moth. A mother.

Moths were, in fact, the lifeforms that most blew me away at Los Cedros. The main building at the research station is an open pavilion with a few generator-run light bulbs fitted onto the pillars supporting the roof. I had never seen anything like the Biodiversity, with a capital B, as demonstrated by those moths, both whirling around the lightbulbs and resting, like jewelled, almost gaudy, brooches on the pillars below. There were literally 50 to 100 species of moths on each pillar - every improbable variation, in colour, shape, size: wings like stained glass, wasp mimics, bark mimics, leaf mimics, candy-cane mimics, pompom feet, twiggy feet, stripy, spotty, fluffy, metallic, hallucinogenic…

Of course, in some ways, it was the extremely remote possibility of seeing a bear at Los Cedros that most quickened my blood. I had brought with me a wildlife camera trap, used mostly to monitor hedgehogs in my garden. I took it up the mountain to the crossing of the Bear Trail (so named for obvious reasons). There were no recent reports of bear sign, but our superb guide, Martín Obando, showed me footage of a bear eating fruit in a copal tree, taken with his phone only a few months before.

There was so much to absorb my attention on that beautiful Bear Trail - too many marvels to enumerate, but Dracula orchids, mushrooms like cat’s tongues, vines like cascading red liquorice bootlaces, ferns like lace, iridescent hummingbirds, centipedes, keening toucans. So I was completely shocked by my bear encounter when it happened. I turned a bend in the trail and there, in front of me, was the unmistakable, overwhelming scent of bear. My eyes and ears could not corroborate my nose in the thick surrounding vegetation, but I would have bet my life that there was, or recently had been, an Andean bear precisely in that place.

It’s a smell I can’t describe very well. It’s like nothing else. Most like a strong smell of leaf litter in the woods, but sweet and a bit baked, and yes, musky, but in no way doggy, skunky or foxy. I have trapped and radio-collared Andean bears, and couldn’t resist burying my face deep in their fur. Really, it is the best smell I know. So I wasn’t wrong, as much as you might think it was wishful thinking. Later I found fresh bear scats on that trail.

“You smelled a bear?” I’m not sure my son and other expedition mates knew quite what to make of my excitement.

•

Between the truly delicious vegan meals and the volunteer work, there were many adventures, best of all to waterfalls where we swam and drank straight from the river. We were also each absorbed in pursuits of our own. Susan used charcoal to draw the forest and portraits of the staff as gifts. Quinn honed his pingpong skills against another volunteer who had literally been a professional pingponger. Quinn also bounced wildly between fascination and horror about the mere idea of the tarantulas and snakes at Los Cedros. My son, Theo, was inspired by ‘Song of the Cedars’ and went on quests with Quinn to record various forest sounds. My own creative endeavour - these days I have a business making wild nature-celebrating wallpaper and printed linen - was a new design all about gazing up into the cloud-forest canopy. I had the most idyllic work station of my life as I sat and sketched and schemed, on a balcony overlooking all that splendour, swallow-tailed kites surfing on the wind, and dwarf squirrels cavorting through the tree ferns.

In our second week at Los Cedros, Martín and I hiked up to camp at the ‘Bear Platform’. The rains are heavy this year - climate change causing drier dry seasons and wetter wets. Trees are falling, overburdened with epiphytes, especially water-collecting bromeliads (imagine giant pineapple tops). The soil is loose like stew that has been over-thinned into soup. Everything grows incredibly fast with all that limitless moisture and solar radiation. Martín had to wield his machete constantly, reopening a trail used just one week before. It was here, while they were using chainsaws in the construction of the platform, that he filmed that bear, seemingly unperturbed, in a nearby copal tree (thoroughly confounding my ideas about how to see bears, by the way!). It is a thrilling trail including vertical rope ascents, but it is mostly muddy and steep, tunnels and archways through trees, many of which feel decidedly portal-esque, for those so inclined. No bears spotted, but non-stop wonders.

From up top, the vistas are made more enchanting by gauzy mists, revealing and concealing again the curves of the mountain. Like expertly deployed lingerie in an extremely slow and serene striptease. Very occasionally a volcano emerges in the distance, bathed in aureolic light, before ducking coyly back into the mist.

Years ago, at the higher elevation of my study site in Bolivia, the cloud was much thicker. My vision was often occluded for most hours of the day by white condensed water vapour, as you might have experienced when flying into thick cloud, such that I could sometimes barely see my hand at the end of my arm. What remained to admire were the regular formations of mosses, the rococo fiddleheads of ferns, glistening lichens and their patterns as they draped themselves artfully on every surface. My contemplation of these exquisite ornamentations, with nothing else to see for hours at a time, seems to have fundamentally rewired my brain.

I started out as a young biologist hunting for the singular great beast, the bear. After 10 months of solid mostly solitary effort, I succeeded in becoming the first person to trap and radio collar wild Andean bears and monitor their movements and activity with radio telemetry. But I realised in time that, though my bear hunts were still fascinating, I was nourished at least as much by the gathering as by the hunting. I gathered data but also a kind of soft-focused delight in the baroque profusion of nature. The minutely interwoven multiples, the relationships, the negative space. Get rid of the frame around the one important thing and be immersed.

I didn’t know what it would feel like, bringing my older, maternal and now fully pattern-centric self, back to the cloud forest where so much began for me. What would it be like for my son? But now the results are in: it was pure magic. I realised that parts of myself that I had assumed were dead were only dormant. They had been sleeping, dreaming, in darkness. It was possible to open the doors and gently wake everyone back up. All the portals. All the selves. For minimalists it might feel right to simplify and strip away. But nature is the ultimate maximalist, and beckons in a way that I, personally, find irresistible.

If you think a friend or loved one would enjoy The Clearing by Katherine May, gift subscriptions are available here | Website | Buy: Enchantment UK /US | Buy: Wintering UK / US | Buy: The Electricity of Every Living Thing UK / US

This newsletter contains affiliate links.

Wow! Stunning essay. It gives hope to those who, for whatever reason, live in circumstances where each day blends unrelentingly into a repeat of the same; all is not lost. In the meantime, Substack offers portals of escape for the mind, like this beautiful writing.

Love this with all its textures, sights and sounds, thanks... I long to be back in those south american cloudforests and pine for Equador...what an amazing place and lets hope for a spreading of the MOTH visionary way forward regarding rights for the more than human and the creativity inherent in these wild places.