See below for forthcoming live events

I always see November as a kind of wasteland: drab weather; the cold beginning to bite; the impending slog of the run-up to Christmas. It is the time before the lights are lit, but the sky is nevertheless grey, a month of foreboding. By the end of October, the woods were full of mushrooms, thousands of curious little figures. November will see to that. Soon, it will all be gone.

The ash tree that overhangs my garden is enduring its leaf-fall. It does not change colour like other trees, but instead drops its entire crown in one fell swoop, like a sudden blizzard. Soon, I will undertake my favourite garden of the year, which is to get out my rake and pile all the leaves over my flower beds, ready to form a mulch. November blankets the garden for winter. Despite its austere demeanour, it is a nurturing month.

This November is particular, though. Never has a month felt more transitional. As I write, we are all anxiously awaiting the result of the US election, and what feels like two divergent realities in prospect afterwards. This is a month of biding time, of finding occupation for disquiet hands. We are cramped up like springs, ready to uncoil into whatever action seems necessary. We can only hope we’ll understand the next steps when they come.

It is not just the election: the whole world seems in disarray. War is spreading, the horror hardening in us like a mineral. The weather is all wrong. It feels as though that sharp November bite might cure us of something, but it is entirely absent this year, and I keep sweating through the knitwear I don out of habit. In Valencia, near my mother’s village, there have been floods so fast and high that hundreds of lives were lost. We have lived through an age of prophecy, and now here it all is, all at once.

And yet we are not powerless. The grey days of November start with All Saints’ Day, the day traditionally attributed to the Christian martyrs. It is in urgent need of a secular revival: a day to remember the myriad people who are rescuing us right now, who are surging into the world’s danger zones, who are keeping their patience as the crowd shouts incoherently back. If any month symbolises hope in dark times, it is November.

And then All Souls’s Day, the day of the year to remember the mundanity of grief, to feel our sadness regardless of how long ago it landed. It used to be marked with the baking of soul cakes, dense little pucks of spiced flour and lard, given to those who were grieving. I made them once, and didn’t particularly want to ever eat them again. But instead, on Saturday morning, I baked a round of shortbread instead, marking it with the traditional cross. It made a more welcome gift, and my palms were soothed by the kneading.

I always fill November with making. I started early with pumpkin chutney and pumpkin pickle, using up the Halloween glut. A funny story: my Polish friend took her mother to the local farm that sells Halloween pumpkins straight from the field. She watched in horror as my friend filled her barrow with 17 beautiful specimens for her front garden. ‘What Western decadence is this?’ she asked, appalled. My friend is now trying to find a way to cook 17 pumpkins to justify her exuberance. I sit on both sides of that fence, which is why I’m cooking too.

Later in the month, I will make my Christmas cake and Christmas pudding, perhaps also mincemeat if I’m restless enough. Soon, my shelves will be full of labelled jars, and I will smile every time I look at them: the ordered pleasure of a stocked larder. All is safely gathered in.

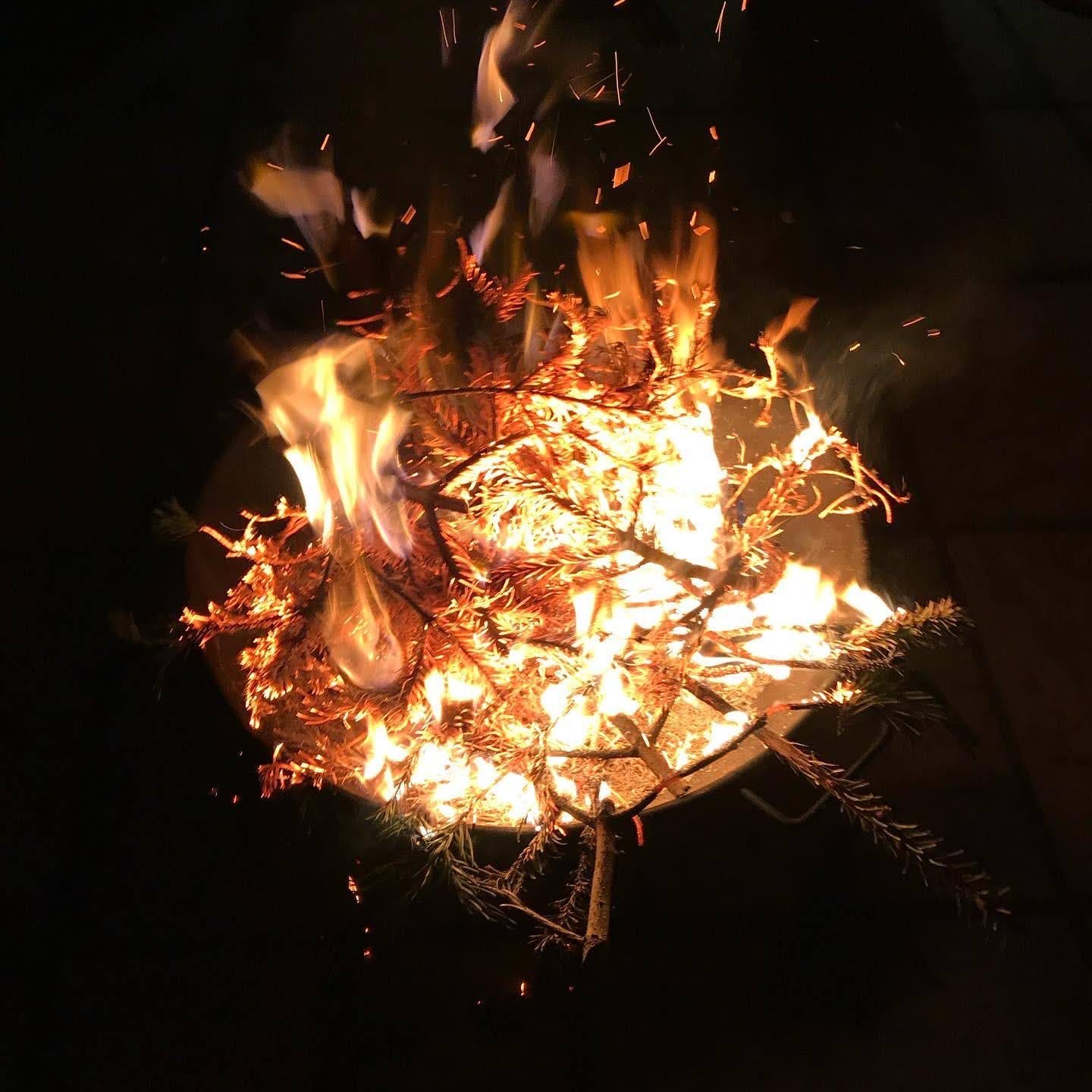

But first: fireworks. It feels only fitting that the most important vote of our global lifetime will be happening as explosions fill the British skies. Bonfire Night is not for me; too loud, too unpredictable, and its witchery runs in the wrong direction. I always love Elspeth Barker’s description in O Caledonia, though:

‘Fortunately, at St Uncumba's Halloween was not celebrated, for it was an evil, pagan ritual. Instead they lit an enormous bonfire on Guy Fawkes night and burned a human effigy. How they cheered and clapped as the guy smouldered, blazed up and sagged forward, collapsing inwards, horribly real. 'It's always an anxious moment, waiting for him to catch,' confided the housemistress. Janet watched the figures round the fire. Squat in their winter boots and heavy coats and scarves they looked like peasants from a Breughel painting; they were intent, mesmerised by the flames, by the pitiful burning figure. A mob, she thought, mob violence. She remembered the organ stop which was called Vox Populi. She wanted none of it.’

Like the glorious heroine Janet, I want nothing to do with mob violence. Let November bring us balm.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Clearing by Katherine May to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.