Hello,

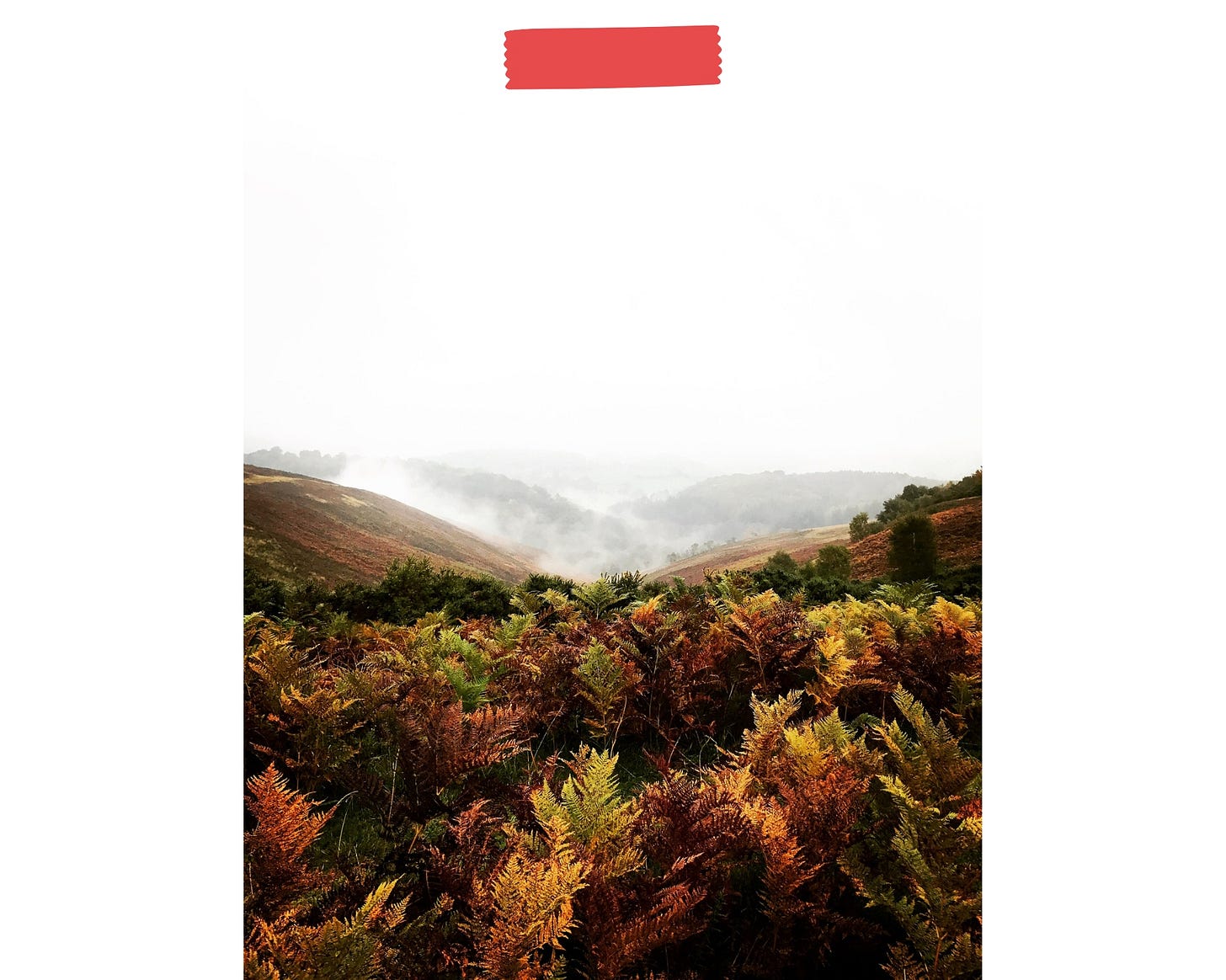

In autumn, my thoughts turn to walking. It’s just the perfect time of year: not too hot, not too cold (yes, I am Goldilocks, thank you for noticing), and just absolutely gorgeous in any number of ways. The ground is not yet horribly muddy, and the rain, when it falls, doesn’t contain shards of ice. It’s all so inviting.

But there’s a more subtle reason that autumn is connected to walking. This is a season when change is visible, and walking is intimately connected to metamorphosis. Long walks, in particular, take us deep within, inviting reflection, reframing and reimagining. That’s why we’re often drawn to hikes and treks at life’s key turning points: they open up the space we need to transform.

I wrote about my own long walk of discovery in The Electricity of Every Living Thing, and a key component, for me, was learning to walk for many hours at a time over difficult terrain. I didn’t begin or end my journey as any kind of impressively fit person. In fact, I carried several chronic conditions with me all the way. But I wanted to walk, and so I figured it out as I went along.

Since that time, lots of people have told me that they’d love to walk themselves, but they don’t know how to get started. So I wanted to share here a bit of what I’ve learned over the years, and hopefully invite as many people as possible to have their time in the wild.

This is my very personal and idiosyncratic guide. It’s going to get detailed. Buckle in.

Getting started

The first and most important thing I want to say is this: bring your actual self to the walk. Not the body and mind you think you ought to have, or even the one you want to have. Start where you are, be honest, and be kind.

Think about any physical restrictions or constraints you have, and make realistic plans. Work your way up gradually. Don’t take risks with your health. If you need to, talk to your doctor about your concerns. Shame often leads us to make unrealistic decisions about physical activity, and, honestly, it’s not worth it.

This is a post about moving your body for pleasure and joy; to seek solitude or the close company of others; to find a slower pace and see the world in detail; to go to places that can’t be reached by road. I will not be referring to it as “exercise”. When I’ve written about walking before, I’ve got heartily sick of people speculating about calories burned and asking if I lost weight. I will not be talking about these things, and I ask you, please, to keep diet culture out of the comments.

I say that without judgement. So many of us have scars that need to be healed in this area, and I know that my eating disorder brain reared its ugly head when I first started walking seriously. But I now see walking as something I do in defiance of the culture of weights and measures and self-loathing, and everything I write here will be from that perspective. I walk to reintegrate, to experience beauty, and to change myself from the inside, not the outside. If nothing else, I hope I can pass this on.

What do I mean by a long walk?

It’s subjective. The “long” is really about time rather than miles. In this post, I’ll be talking about walks that take half a day or more, or walks that require a bit more planning than a stroll from your front door.

It took me a long time to realise that thinking in miles is quite misleading. Walking ten miles on the flat is very different to walking ten miles in hilly terrain - the first might take me three hours or less; the second could easily take ten or more.

In any case, who’s counting? I’m not getting into any competitive bullshit here :)

Planning your walk

So, a walk is calling you. You’re either craving a certain landscape, or some time on your own. Or maybe there’s something else, an itchy feeling that says you need to move your legs. Here are some things to consider:

Spend as much time as possible researching your route - and buy a good map so you can trace the route with your fingers (in the UK, Ordnance Survey Explorer maps are best for walking). Even if you’re planning to use an app for your mapping, I’d urge you to bring a printed copy too. If you don’t have a signal, you’ll have a backup. I have an absolutely terrible sense of direction and I don’t always pay attention, so I try to follow marked trails if I can. It just makes everything that little bit easier. (If you’re not used to reading maps, there are some great beginners’ guides here - but to some extent, you’ll only be able to learn through experience.)

Do you want to walk alone, or with others? Think carefully about this - not everyone is your ideal walking partner, if you know what I mean. But walking with a dear friend can be a wonderful experience. Just make the choice consciously. When you talk about your walk, some people will ask to come along. You don’t have to say yes. Here’s my full permission to say, “I’m doing this one alone, but maybe another time.”

How will you get on and off the trail? Will you walk from A to B, or circle back to where you started? If it’s the former, plan how you’ll get back to civilisation - can someone collect you? Is there public transport? Do not assume that you can spontaneously call a taxi in rural areas - but you can sometimes book in advance.

Check out early exit routes. It’s hard to predict how a walk will go: adverse weather, equipment failure, injury, exhaustion, the route taking longer than you expected, or just not feeling it… there are lots of reasons you might need to stop early. Make sure that your route has options for an early finish, or to cut corners on a circular walk.

Research the disreputable end of the local flora and fauna, and how to avoid/repel them. I don’t just mean wolves and bears - it’s important to know how to pass through a field of cattle without upsetting them. Ticks are an increasing problem, and you need to know how to avoid them, how to remove them and how to spot a ‘bullseye’ rash.

Timing

It’s useful to know in advance how long a walk will take, but in practice this is far from simple.

Walkers often rely on Naismith’s Rule, which says that you should expect to walk at 3mph/5kmph plus an extra hour for every 2,000 feet of ascent.

It seems to me that this is mainly useful for calculating how fast Naismith himself walked. Lots of people have added corrections and amendments to this formula, and it becomes headache-inducing quite quickly.

Let go of the idea that you can predict the duration of a walk with any accuracy. However, it helps to have a rough idea. I go through these steps when I’m trying to work out the timing of a walk (it goes without saying that you should calculate for the slowest walker in your group - you don’t get to leave them behind!):

I use a piece of string to measure the actual length of the walk on the map, not “as the crow flies”. This really matters on squiggly paths like coastal paths.

I know how fast I walk on the flat, and I use this to calculate a baseline speed. I cannot emphasise this enough: this will be different for everybody. Some very experienced walkers are really quite slow compared to Naismith’s metric, and you might want to stop more often to look at the sights. Don’t get all up in your head about this. You are not trying to set any kind of world record; you’re trying to have a nice time. Take an hour’s walk at a comfortable pace, time yourself, and see how far you’ve gone. This is your baseline speed. Multiply this by the number of miles in your walk.

I then look at my route again, and add 20 minutes for every contour line I cross, up or down. When I first started walking the SWCP, I could not believe how long the steep parts of the route were taking me; this formula helped me to understand why. It might overestimate the impact of some ascents and descents, but it’s not far off. Don’t assume that you’ll make up time on descents; it takes ages to climb down a steep hill (and it hurts your knees way more).

Add in time for rests and lunch. I usually stop every 90 minutes for 15 minutes or so, but I might also need to take a few moments after climbing a hill, y’know.

Work with ranges, not precise numbers. All kinds of things can happen on your walk. You might be walking into a headwind. The path might be busy and therefore slow. You might feel full of energy that day and not need a rest. Calculate your walk time as a realistic range: the fastest time you could do it, and the slowest.

Think about what this means for your walk: will it still be light when you finish? Is the weather due to change during the day? If the going is slow, is there an early exit point on your trail? How will your timings affect your access to transport?

Consider carefully about how this will all work, and whether you need to alter any plans.

Most of all, leave space for nice surprises. You might spot a magnificent animal or bird, or you may want to spend some time admiring the view. If you’re me, you might occascionally take off all your clothes and run into the sea in remote coves. Much better to do these things than to watch the clock.

Safety

Walking is a pretty safe activity in the scheme of things.

I mostly walk alone, but I only do that in landscapes where I understand and feel safe within the politics and culture. I feel safe as a solo walker. However, I am a white and can pass as neurotypical, which helps. The barriers for women, LGBTQIA+ folk, people of colour and other minority groups in accessing rural areas are real, and that’s without factoring in the physical barriers that many people face. If in any doubt at all, bring others with you. Brilliant groups like Flock Together are leading the way in creating access to the wild by going out en masse. Check out groups near you.

Only you can plan your walk, based on your own experiences and comfort levels. If you feel anxious, that’s completely okay. Ignore people who tell you not to be silly. Your walk. Your parameters. None of their business.

There are other safety issues that you should consider though:

In unfamiliar terrain, I’d join a group excursion or take a local guide. Don’t be ashamed to build a skillset.

Check the weather forecast and make a serious assessment of whether your route will be safe on the day of your walk. Think about slippery paths, high winds, and the chance of getting stranded. In remote places, the weather can change very quickly. Be ready to cancel if it’s not safe.

Remember that hot weather can be just as dangerous as winter weather. If you feel happy to walk in high temperatures, ensure you have plenty of water, slather yourself in sun cream and wear a hat. I also like to wear a cotton scarf to protect the back of my neck.

Tell someone your route and expected timings, and agree to check in with them at a certain time. Bear in mind that you may not have a phone signal along the route. Agree a plan with them should they not be able to contact you.

Listen to local advice about things like tides and path conditions; don’t ignore warning signs. I’ve seen people amble past signs saying “Danger! Cliff Fall!” to get a better look. Seriously. This is not a theme park.

Be prepared for changes in conditions. Carry something warm, something for wet weather, something to eat and something to drink. See below for what I pack.

Ultimately, the best way to keep yourself safe is to take your ego out of the walk. Nature is bigger than you are. Stay comfortably within your own limits, and don’t worry about the adrenaline junkies and the super-fit - they might just have different limits to you. There’s space for all of us.

If you’re anxious about being out in the wilds, build up slowly and stick to well-marked paths, close to civilization at first. Things will always go a bit wrong when you’re walking, so, over time, you learn to be flexible and to problem-solve.

Kit

I don’t think that most walkers need to buy significant kit at first. You’ll need a comfortable backpack, sturdy shoes or trainers with a good grip, and maybe a folding waterproof jacket. It’s better to go out and take a nice walk in the woods using exactly what you have, rather than convincing yourself that you have to wait until you can afford to spend hundreds on the right stuff.

If in doubt, just go for a walk.

However, if you’re going to invest, here’s my personal take on walking kit. (Just for your info, there are no affiliate links here - this is genuinely what I use.)

Footwear:

You don’t necessarily need boots. In the summer, I prefer comfortable trainers for most walks, and I sometimes wear barefoot toe shoes, which I love because they let me bend my feet, which can make it easier to balance and grip dusty rocks. I know some of you will find them horrifying, sorry. (I draw the line at these though.)

If you’re buying specialist footwear, don’t order it online. Go to a good outdoor store where they will fit it properly, and really spend some time trying on a few pairs and seeing what feels comfortable. They should feel like putting your feet into clouds; even the smallest discomfort will amplify over long distances. I always buy a size too big, partly to accommodate chunky socks, but also so that my toes still don’t hit the end when I’m walking downhill. You may also find that your feet swell over the course of the day, so you need a little extra room.

In winter, I now wear hiking shoes, which keep my feet stable and have soles with deep grips to power through mud. I had so much trouble with boots giving me blisters, and I gave up. My current ones are by Oboz - I have a very high instep and I absolutely adore them, but everyone’s feet are different. H, who won’t mind me saying he has wide, flat feet, swears by Merrell.

Boots come into their own on uneven terrain where you’re at risk or turning your ankle, or when there is likely to be a lot of mud. They’re also great for people whose ankles have a lot of movement in them. In the past, I’ve had pairs made by Asolo and Meindl, which have been great, but then my feet changed after I was pregnant and I’ve found them uncomfortable ever since.

Most of all, don’t buy cheap boots. It’s better to just wear shoes you already know are comfortable than to buy boots that aren’t completely excellent. It’s such a false economy: they will fall apart, cover you in blisters, leak, and put you off walking altogether. And I don’t care how comfortable you find your wellies, do not wear them for walking. You will either get trench foot, or plantar fasciitis, or both.

While we’re here - a quick note on blisters. Do all you can to avoid them - and it is possible. Good socks and properly fitting boots will go a long way. Make sure that your feet don’t move in your boots when you take a step, because friction is your enemy. If need be, adjust the fit of your boots with insoles and stick-in padding, and change those insoles regularly. If you do get blisters, make sure they’re properly dressed before you walk again. I rely on the gel blister plasters for smaller blisters and I always carry them with me. For bigger ones, I pad them out with non-stick dressing and surgical tape. I’m not going to wade into the debate about whether to burst them or not because it gets heated and gross. I know that some people swear by Vaseline, but this seems to me to be a capitulation to the boots moving against your heel in the first place.

Socks:

Invest in a good pair of socks: go for a cushioned sole and a nice firm band around the arch for support. I like long ones that I can pull up over my calves, but that’s just a personal thing. Proper wool socks are lovely, and great for managing temperature and moisture, but I am not sufficiently good at laundry to buy any more. After pulling my fifth pair of felted, miniature socks from the washing machine, I conceded defeat. I still yearn after these, though.

Underwear:

Two words: wicking knickers. You’ll thank me.

Clothing:

Many, many people have tried to talk me out of this, but I always walk in a cheap pair of running leggings that I bought for £10 in about 2008. They have seen me through all weathers, they don’t catch on brambles, and I can pull my socks up over them to defend against ticks. I wear a sports t-shirt on top (again: wicking), and I add a thin top layer which usually gets too hot quite quickly.

You don’t need fancy walking clothing - just pay careful attention to seams. If there’s a possibility of rubbing, it will happen, and it’s horrible. That’s why running leggings are so good. If I ever decide to upgrade, I’ll get the ones with a bit of compression built in, but right now I can’t say goodbye to my old friends.

If running tights are not for you, then wear something that dries easily, and which isn’t too baggy. Please, please, please do not wear jeans unless you want thigh blisters. If it rains, they will weigh 100 tons (okay, that might be a slight exaggeration) and will not dry out until Judegement Day. I don’t think I can express myself in any stronger terms.

Outer layer:

It’s much better to have multiple thin layers than one big, fat jacket. You get surprisingly hot when walking, even in cold weather. I always carry a waterproof, but most of the year it’s a cheap pac-a-mac. In the winter, I bring a more sturdy jacket that’s designed for walking, but it’s much more bulky and I’d rather travel light if at all possible. If you’re buying a jacket, make sure it’s waterproof (not just showerproof), breathable, and has a hood.

Hat:

Something warm for winter and something that protects your head for summer. And yes, I am now your mum.

Backpack:

It’s worth getting one that is properly fitted to your back. Unless you’re carrying your own tent and food (I have no experience of this, ask Cheryl Strayed), a light “day pack” should be enough - big backpacks can get very sweaty. Straps can rub over the course of the day, so make sure yours are padded.

Water:

Lots of walking backpacks now come with a pouch for a water bladder - basically a big, stong plastic bag with a pipe for drinking through. These are a great idea, and much easier than carrying bottles. However, as long as I know I’m passing a source of fresh water (a river or a lake), I now carry a Grayl instead. This is an incredible little filter that will purify water on the go, meaning that you don’t have to carry it.

Whatever you choose, please stay hydrated. I know it sounds obvious, but then I’ve also met lots of people who’ve sought to avoid drinking too much while walking because they don’t want to carry it, or don’t want to have to pee outdoors. It goes without saying that drinking water can prevent heat exhaustion, sore muscles, cramps, headaches, and also feeling thirsty, which is pretty unpleasant in itself. Drink water as you go, and learn to pee outdoors. It’s one of life’s small joys.

Walking poles:

I don’t carry walking poles, but I have tried them and they do help. However, I am stubborn and afraid of tripping over them, so I will continue without them for the foreseeable.

What to pack on the day

WATER - in case I haven’t made myself quite clear.

Food - when I was first walking the SWCP, I tried not to eat anything (see above - eating disorders are hard to shake), and I am here to tell you that this was not a good decision. Walking is hard physical work and your body needs fuel. I got not only exhausted but also confused (I couldn’t even count to 10), which was dangerous in a remote location. I learned my lesson. I now always carry peanut-butter sandwiches with cucumber, because they still taste ambrosial if they’re squashed in the bottom of your bag. Along the way, I snack on Peanut M&Ms because they are excellent little packets of energy and deliciousness, and I tend to carry a couple of cereal bars too. Bring enough food, and some to spare. Eat.

Lip balm and a sun-cream stick

First aid - I don’t carry a lot, but I carry gel blister plasters, antiseptic wipes, a few plasters, paracetamol and antihistamine, plus a spare set of my regular meds just in case I forget in the morning.

My map. If it’s raining, consider getting a plastic map cover, or use one of those transparent file envelopes.

A compass - retro I know, but you can’t depend on your phone. I use it very rarely, but it can really help when you’re lost.

A thin, warm layer - if I stop to eat, I put this on with my waterproof over the top so that my muscles stay warm.

My notebook and a pencil.

Apps etc

I always bring my phone on a walk, and make sure it’s well-charged - but experience tells me that I’ll never have a signal when I want one. For this reason, download all your apps in advance.

Apps you might want or need:

A mapping app - download the map for your area in advance. I like the Ordnance Survey one, but other people don’t, so I guess it’s a personal thing.

What Three Words - this is an excellent way of sharing your exact location, should you get a bit lost and also happen to have a signal.

WhatsApp - I turn off notifications while I’m walking, but it’s useful to have this in case I need to send a message out. WhatsApp is useful because it will find a window to send your message if it can; I find that texts just give up trying after a while.

Plant- and bird-identification apps - nice to have, just in case you spot something interesting.

A voice-recording app to capture ideas while you’re on the move.

But mostly, stop looking at your phone and take in the scenery.

Bitter experience compels me to say: don’t carry your phone in your pocket. If you carry it in a side pocket, it will dig into your leg. If you carry it in your back pocket, you will crush it if you fall over. I once lost a phone to a sudden storm just outside Bude. The initial hailstones smashed my screen, and then rain that followed got into the cracks and broke it for good. Keep your phone safely in your bag, and get it out when you need it.

Technique

Ugh, I am so sorry to include a section called “technique” - just walk and stop when you’re tired, yes?

As an aside, I went walking with my lovely editor Jynne in the Catskills last year. Jynne spends her free time trekking across the Antarctic and climbing sheer rock faces carrying 50lb packs (I’m not even joking). I, on the other hand, have lungs that have never been the same since my first bout of covid. Jynne and I set off up a small mountain, and after a while she stopped to look me over with amused eyes. “What you do,” she said, “is go full pelt for five minutes so that I can barely keep up with you, and then look as though you’re either going to puke or pass out. Then you do it all over again.” This is absolutely true. The only mystery is how she didn’t guess that after working on my writing for a few years. This is how I approach all of life.

So, I am the last person you should listen to when it comes to technique.

But there are a few things I’d note, which might help:

I love hills, but some of them want to kill me. The best way to approach them is to take many small steps, lifting your knees as if you’re climbing a staircase. Tuck your bottom in to engage your core (hi, my pilates teacher, and thank you!), and imagine a string is attached to the top of your head, pulling you gently upwards. Convince yourself that you’re floating. It honestly helps.

Stretch at the end of difficult bits, climbs or descents. When I’m on the flat, I take extra big strides to stretch out my legs.

If your fingers get swollen, lift your hands over your head for a while to drain them. This is quite normal.

Don’t take your boots off along the way. It might seem really tempting to paddle in a stream or feel the grass between your toes, but they’ll feel awful when you put them back on again. Those boots are part of your body now, at least until you’re home. Obviously break this rule to dress blisters.

If you’re exhausted and you’ve already eaten something, drank water and taken a rest, there’s a runner’s technique to keep you moving. Visualise walking from your skeleton, rather than your muscles - you’re just a framework, moving like a pendulum. Tick tock, tick tock, you keep going forward.

Don’t use headphones while you’re walking. I know lots of people worry they’ll get bored, but that’s part of what you’re doing here: giving your brain a chance to do its own thing. Let yourself experience the walk and its beautiful soundscape; allow your thoughts to roam. This is partly a safety issue, but it’s mostly a pleasure issue. Be there on your walk, not somewhere else in your head.

However, if you’re really struggling at the end of a walk, music can help to get you through that last mile or so. If it’s safe, I concede that it’s okay dig those headphones out.

Recovery

It’s normal to feel really, really tired after a long walk. Keep the evening free.

Change out of damp clothes as quickly as possible - your temperature can drop once you stop moving. If you can bring a change of clothes in your car, do - including shoes and socks. There is nothing much nicer than changing into something warm and dry after a wet day’s hike, and I will merrily strip off in car parks to reach this perfect state of being. Own a onesie? Bring that.

Even if you don’t feel sore directly after the walk, your muscles can feel very stiff and painful the next day. This can mostly be avoided by doing running stretches directly after your walk, drinking plenty of water or an electrolyte drink (even after you’ve finished), and eating a good, balanced meal including protein, carbs and veg. A lot of people swear by foam rollers to massage their muscles afterwards, but I’ve never tried it so I can’t comment. However, I do take ibuprofen/Advil after a long walk to reduce inflammation (obviously only do this if you can tolerate it).

Warm baths are very nice for tired muscles, but ice is also great: a cold swim, an ice pack on painful joints, or, if you’re feeling truly brave, an ice bath. I’d personally rather not.

OK, that was long, but I hope it was useful. Let me know your walking tips in the comments - and I’ll do my best to answer any questions. Happy trails!

Take care,

Katherine

If you think a friend or loved one would enjoy The Clearing by Katherine May, gift subscriptions are available here | Website | Buy: Enchantment UK /US | Buy: Wintering UK / US | Buy: The Electricity of Every Living Thing UK / US

Brit, living in US, and currently visiting Devon. Channeling our inner Katharine May, we just walked a chunk of the SWCP from Hope Cove to Bolberry Down, followed by a wild swim at Hope Cove. We're avid hikers back home in Washington State, and while there are great trails in the North Cascades and Olympics which we love, walking around the edge of our home island in Puget Sound means walking along the tide line because "private beaches".

On the other hand, we're also avid cyclists and our island is a haven compared to the roads here!

Absolutely agree with you! I feel so appreciative of the fact that one could literally walk the whole perimeter of the UK safely. I walk a lot on my own and although I still prefer to have my dog by my side in places I’m not 100% familiar with, I’ve never ever had bad experience compared to other countries, that I’m not going to name