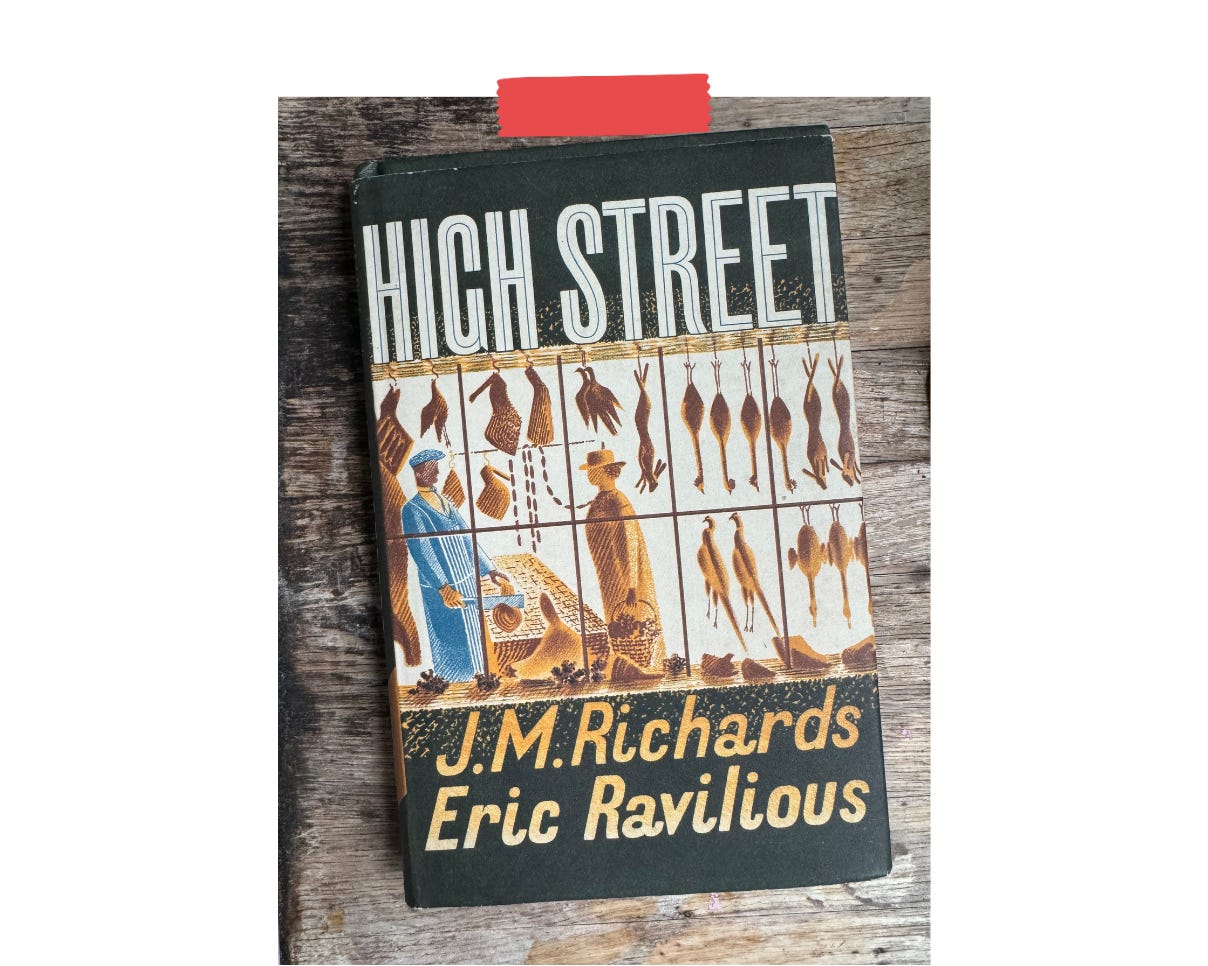

Last week, I went to see an exhibition called Living With Art at Canterbury’s Beaney Museum, and my eye was caught by a series of small lithographs at the far end of the gallery. Drawn by Eric Ravilious, they each illustrated a shop or restaurant in a pastel-hued town. The prints were published in a 1938 book called High Street, and on discovering that original editions sell for around £5,000, I ordered a facsimile edition when I got home.

High Street is a curious book; its purpose is hard to place. The illustrations are delicious, showing shopfronts like rows of confectionery, their workers neat and solemn and absorbed. Its text, the work of architectural writer J. M. Richards, can only be aimed at children (‘This is a book of pictures of different kinds of shops,’ it opens), but it is hard to imagine the child, now or then, who would be persuaded to plough through its many pages of dense descriptive prose.

For an adult, though, it’s a different matter. The text evokes a time that feels distantly familiar to me; I only know it by its dying. It falls within my saeculum, the hundred years of memory to which we all have access through our oldest living relatives (Rebecca Solnit makes a wonderful account of it in Orwell’s Roses). The kind of shop that is shown in this book was still present in my childhood, but only as a distant memory. This was the era that my grandparents had known, before their world changed forever.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Clearing by Katherine May to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.