Hello,

People quite often ask how I decide what to put in my books. Honestly, it’s mostly trial and error. I write a chapter or segment and see if it goes anywhere. For Wintering, there were a few bits and pieces that I couldn’t get to work. For Enchantment, there was a whole graveyard of rejected material.

There’s nothing wrong with most of it. Quite often, the tone feels immediately jarring, like it belongs in a different book, or takes me in a direction that I don’t want to go. In some cases, my editor just won’t like a piece as much as I do. I’m relaxed about this - I see writing as an act of abundance, and I’m willing to ‘waste’ hundreds of thousands of words in order to find exactly the right ones.

Occasionally, though, a story will stay in the book across multiple drafts, and then suddenly feel out of place somehow. Everything else has moved on, but it has stayed the same. That’s what happened with the piece below - I really like the story and the arc; it’s just that, when Enchantment approached its final form, I could no longer see where this could fit. The tone is a bit different to the rest of the book, and its positioning at Easter didn’t fit with the subtle timeline I was building. It simply didn’t belong. I promised myself that I’d put it into my newsletter instead once the book was published.

So here it is. It’s got everything really: Star Wars, Easter, and the power of mythologies. Enjoy!

Over the Easter weekend, Bert comes home from school and declares that he wants to watch Star Wars.

H, who has been waiting for this moment now for the best part of a decade, reacts like one of those cartoon characters scrambling on the spot in their extreme haste. ‘Of course!’ he says. ‘Let’s do it! But where do we start? Original trilogy or Episode One? There’s a case for both, but…’

‘Don’t overthink it,’ I say. ‘Start where you started.’

Bert loves movies, but he’s conspicuously avoided Star Wars. His interest has always run in inverse proportion to H’s desperation for him to love it. This means that Bert has an awful lot of Star Wars-based toys rattling around the shelves in his bedroom, and he learned to read from Star Wars primers, but he has asserted his power to refuse to actually watch the films. This has often felt to H like a withholding of love, and several times I have found myself urging H to ‘give him time,’ which always makes me feel like some wise matriarch waiting patiently for my wayward son to see the light.

H has ostensibly stopped begging now, but has carried on drawing Bert’s attention to every new tidbit of Star Wars news as if he’s interested. He often remarks (with a regularity that startles me) ‘I sat up and watched Star Wars last night’ while Bert is eating his breakfast. Bert has been almost stoical in his refusal to be drawn, no matter how many times H has said ‘But there are lasers and space ships!’ Even today, Bert has attributed this sudden motivation to a new friendship at school. The other kid likes it, so Bert is playing catch up. H, ever the pragmatist, is willing to take what he can get.

They settle down to watch A New Hope, and I do what I always do when they watch films together, drifting in and out of the room, sometimes getting snagged on exciting moments of the action, sometimes retreating to the kitchen to cook or make tea. This film, in particular, is not mine to share. It is H’s through and through, a movie he saw in the cinema aged six that has carried on meaning everything to him.

He was one of the 390,127 British people who noted their religion as ‘Jedi’ in the 2001 census, much to my disapproval at the time. I have since come to think that having 0.7 per cent of citizens declaring themselves Jedi probably tells us more about our society than those same people ticking ‘no religion’. It’s all data. In any case, I sometimes think that H was entirely sincere. It’s the closest he’s got to faith. He sits in a confidential huddle with Bert, and points out the minutiae of the text he knows so well, determined that the full resonance of the story won’t be missed. Every new location and character is named and put into context. ‘Just notice that,’ he says every now and then. ‘It becomes very important later.’ The relative merits of Luke Skywalker and Han Solo are discussed. Bert instinctively sees Han as a bad guy, and that has to be unpacked. ‘We’re both natural Lukes,’ says H. ‘But you learn to love the Hans of this world as you get older.’

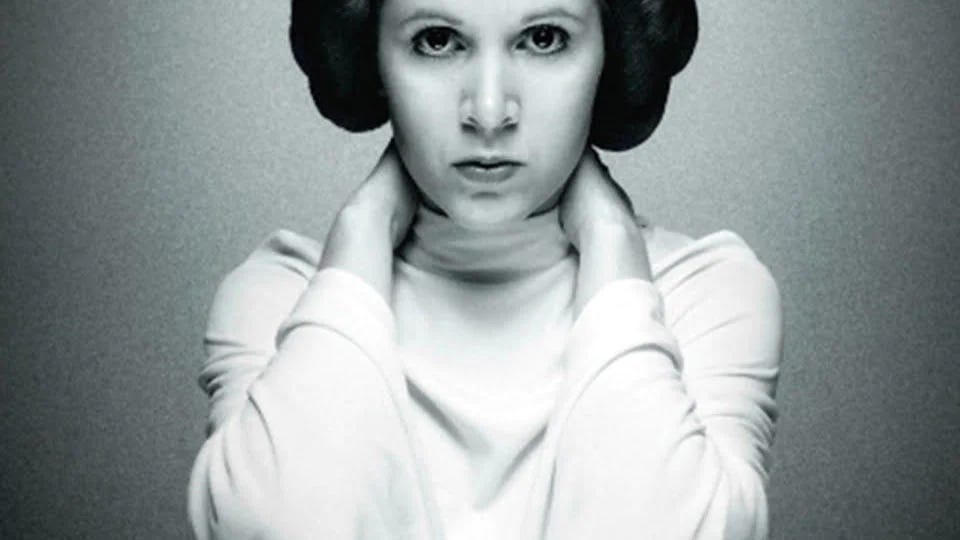

Bert digs out his lightsaber before bedtime, and soon the bedclothes have felt the might of his Jedi fury. The cats scatter, and H spends some time explaining that Jedis only use violence as a last resort. ‘The Force is about tuning in,’ he says. ‘You use it to deescalate conflict and bring about peace.’ I roll my eyes. It is, after all, just a film. Having only really encountered the original trilogy in my late teens, it has never pulled on me as it does on H. I think it’s a great act of the imagination with some good sequences and a patchy script. The whole enterprise is made viable by Carrie Fisher, who also wrote some excellent books, and of course Harrison Ford is uniquely watchable. I point out that he built Joan Didion’s bookcases, but for some reason this falls on deaf ears.

Over the next few days, they move on the The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi. Bert senses of the direction of travel. ‘Does Darth Vader turn good in the end?’ he asks repeatedly. ‘Wait and see,’ says H, at first rather smugly, and then, as the questions continue, with increasing weariness. The point is that Luke has to be tested more first. He has to prove that he retains his purity of mind in the face of total despair, and he has to endure unbearable suffering as part of the path to salvation. It’s biblical, really; the second greatest story ever told. When, finally, Luke has shown his worth and his father joins the lineup of Force Ghosts, I say, as I always do, ‘God, I hate this bit. It ruins the whole story.’

They both glare at me. I have intruded onto a territory that I don’t understand, and I’ve missed the point. In present company, this is no mere film. It’s a mythology. It’s purpose is not to entertain, nor to deliver a satisfying narrative arc. It is there to sneak life lessons past the guards. It is there to allow father and son to talk about being father and son.

Along with a desire to watch Star Wars, Bert also brought home from school a new knowledge of the Easter story. It is not, in all honesty, something that we would have taught him. It feels like part of someone else’s culture, not mine, and I have no reason to share that mythology. The story of Christ’s betrayal and crucifixion is not exactly an easy one to tell to a child anyway. There’s so much cruelty in it. If there’s no belief driving the narrative, then it’s a pretty strange story to tell. I might as well offer him an afternoon browsing the Amnesty International website: the secular lessons are the same.

But then, I chose to send him a Church of England school, and I never thought it would do him any harm to learn a little about religion from the inside. In a world so short on mythological thought, I felt as though the Bible - which I also learned about at school - would give him some structures of thought to work on. If he found he believed, then great; he would have pulled off a feat that I could never manage. If he didn’t, well then maybe he would enjoy rebelling against it. Or maybe, like me, he would come out with a sly sense of partial belonging, and an understanding of that oceanic feeling, but a sense that this wasn’t the right route to it. I thought it would make his imaginative world a little more complex.

This was the first year that he asked about the different days over the weekend - what happened on Good Friday? When was the resurrection? I found myself telling the story myself, in my own words, and with my own remembrance and forgettings. It reminded me of my family’s custom, long-forgotten, of eating fish on Good Friday, and so we brought that back, if only in the form of battered cod from the chippy. It was a small statement of identity, and it unpacked a slew of other stories: my grandmother frying sprats on Good Friday, and the way her generation did not see fish as flesh. The puzzlement I caused when I became a vegetarian, aged eleven, and wouldn’t even eat bacon. The way we used to wait for each new vegetable to emerge from my grandad’s garden, including the new potatoes whose skin rubbed off under your thumb, and the asparagus plant that issued three spears every year, which we shared reverently between us. I can still feel rapture at the sight of a January King cabbage even now, particularly if it carries beads of rainwater. It’s a way of saying: this is where you come from. This is who we are.

As we trace the story of the resurrection over the long weekend, I realise what it means to travel through a story in real time, living its rhythms. Without the obligation to pass it on, I would never have noticed its resonance. We begin by reflecting on betrayal, and the world’s horrors, and then, before redemption can come, our gaze uncomfortably rests on our own faithlessness and doubt. After the relief of the resurrection, that final beat of the story is bittersweet: Jesus comes back only to leave us again. Telling this over a course of a long weekend - between easter egg hunts and hot cross buns - is a reflective discipline that I wasn’t expecting to find. It draws us together, not in belief or faith, but in the act of weaving a metaphorical cloth, both of us chiming in with what we know.

In our largely godless household, though, Star Wars is definitely the main event. Watching Bert and H pore over the relative merits of the supporting cast, I am reminded of the social anthropologist Clifford Geertz’s 1973 essay, Deep Play. Deep play is a game in which the players are in over their heads, usually with money at stake, but also all the matters of status that come with that: ‘esteem, honour, dignity, respect.’ It is, on the face of it, a leisure activity, but one that encapsulates the whole symbolic universe of the people who partake.

Deep play opens up a space in which we can try on new identities and make mistakes before we land our new-formed selves in the real world. It’s another form of symbolic living, a way to transpose one reality onto another, and mine for the meaning. It is through play, and not instruction, that we pass on an intuitive understanding of who we are, the rules we follow, and the values we prioritise. In some houses, that happens through sport or worship. In ours, it comes via the medium of Star Wars.

Wishing you a very happy High Spring, however you celebrate it (or High Autumn for you Southern Hemisphere folk). I’m sneakily on holiday this week, so I’ll look forward to your comments when I get back!

Take care,

Katherine

Upcoming Events

Online

April 19 @ 7pm Faber Members online - in conversation with Cariad Lloyd. Tickets available here.

April 27 @ 7:30pm Boozy Book Club. Tickets available here.

In person

May 15 @ 5pm Bath Festival. Tickets available here.

May 26 @ 6pm Norwich Festival. Tickets available here.

June 3 @ 11:30am Hay Festival. Tickets available here.

June 11 @ tbc KITE Festival. Tickets available here.

June 24 @ 6pm Seven Fables. Tickets available here.

Website | Patreon | Buy: Enchantment UK /US | Buy: Wintering UK / US | Buy: The Electricity of Every Living Thing UK / US

Cannot love this more. My dad dragged me to see all three original Star Wars movies when they re-released them in the late 90s. I was an adolescent and was horrified to be at a weird space film. Except I didn’t end up hating them. I absolutely became obsessed. For me, it wasn’t luke or darth. It was Leia. She was all spitfire and feisty woman and I had never witnessed a female character that mirrored myself. The whole series was the myth my awkward, traumatized self needed.

When I applied to my mythological studies PhD program, I wrote my entrance essay about Star Wars. Some myths will forever shape the core of who you are if you let them. I love that you let all of this unfold in your household.

May the force be with you. (Or happy Easter)

Always!

Really enjoyed that, Katherine 💛 Grateful that it found a home here. And wow the newfound knowledge that Han Solo built Joan Didion’s bookcases has blown my mind—in the best way possible!