June’s (how are we in June already?) True Stories Book Club is on:

Tuesday 25th June 2024

6pm UK/1pm ET/10am PT

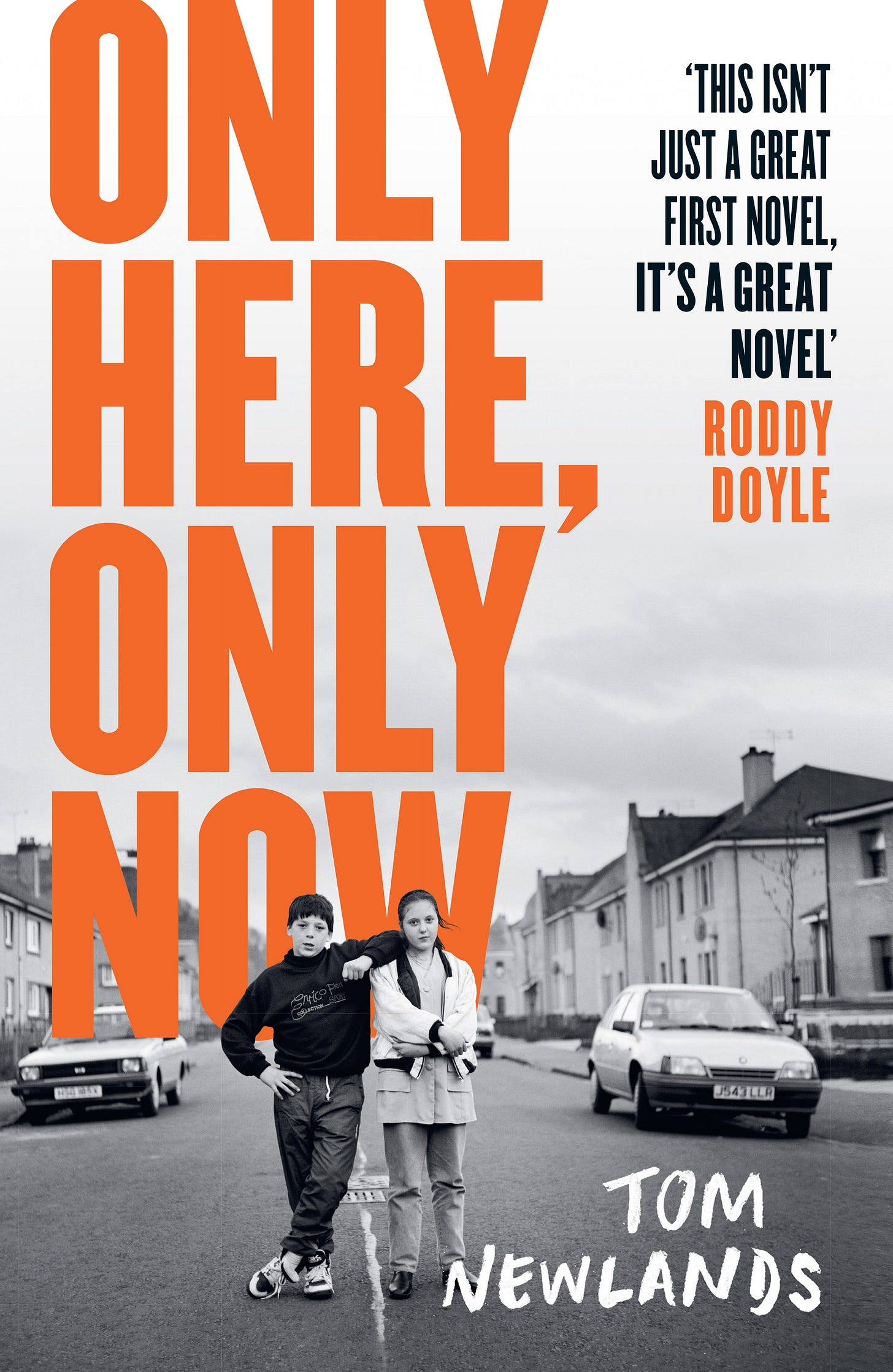

This month’s pick is a bit of an unusual choice for a non-fiction book club… a novel! But Tom Newlands’ debut, Only Here, Only Now captivated me enough to break my own rules. I’ll attempt to explain why below - and there’s an exclusive excerpt at the end of this post too!

Just in case this is your first book club, here’s what you need to know:

Paid subscribers can join us live online for the discussion - a link is at the bottom of the page, after the paywall - and you can send in questions for Tom by posting them in the comments. If you can’t make it live, we’ll post a recording as soon as possible after the event.

Free subscribers can listen to the recording later.

You don’t have to read the book to take part - but however you use it, hopefully the book club will inspire you to find some brilliant new books and authors!

About Only Here, Only Now

I’m asked to blurb an impossible number of books, and so, in general, I only say ‘yes’ to non-fiction. But when I received a note from Tom’s publisher - the legendary Francesca Main - I was intrigued. ‘Tom Newlands is a blazing talent by any measure,’ she wrote, ‘but the fact that he is a neurodivergent, working-class Scottish writer who has never been to university or taken a creative-writing course makes me all the more determined to get his voice heard.’ I called in the book.

I won’t lie: my intention was simply to help out a fellow working-class, neurodivergent author. But when I sat down to read Only Here, Only Now, I was immediately absorbed into a world that felt so utterly real to me, so completely familiar and intricately understood, that I wanted to swallow it whole.

The book is voiced by Cora Mowat, a teenage girl living in a dead-end town in 1990s Scotland. She has plenty of her own problems and big dreams for her future, but when her mother starts a relationship with a new man, her life changes in profound ways. Gunner is an unlikely father figure, having never been parented himself. And yet a bond quickly forms between the two misfits, even as the world crumbles beneath them.

Many things are extraordinary about this book; it’s incredibly assured. Cora’s voice is so perfectly captured that I immediately felt like I knew her; perhaps I do. What I admire most of all is that Tom describes a difficult, compromised life without ever degrading his protagonist. Until I read this book, I didn’t realise what a rare thing it was to see a working-class girl portrayed with so much agency and dignity. Her world is magical in its depth and detail. The whole thing breathes.

You may have guessed already that Cora is neurodivergent herself, and it’s exciting to see this filtering into novels in a different way to the problematic past (which I wrote about here) - integrated into the character in a completely natural, understood way. I felt seen by this novel, and I think that many of you will feel the same way. That’s why I’ve broken the non-fiction rule. It’s a novel, but it’s real. I hope you’ll love it too.

Only Here, Only Now is published on 13th June in the UK and in November in the US - while you wait, there’s a nice, long excerpt below.

Pre-order Only Here, Only Now in the UK

Essential links:

An introduction to Tom’s work by none other than Michael Sheen

About Tom Newlands

Tom Newlands is a Scottish writer living in London. He is a winner of the London Writer’s Award for Literary Fiction, a Creative Future Writer’s Award and New Writing North’s A Writing Chance. Most recently his work has appeared in the New Statesman, New Writing Scotland and in the BBC Radio production Margins to Mainstream, with actor Michael Sheen. His debut novel Only Here, Only Now will be published in 2024 by Phoenix Books.

Here’s an extract from Only Here, Only Now.

Muircross, 1994

It was the second day of the holidays and me and Jo were down the Causeway Field with nothing to do.

The swing park had been cut down when I was nine, so all you saw now was a wee scrap of tarmac with some stumps and a bin and a bench. I was sat there sweltering, picking my knees, squelching my toes inside the Reeboks. All you could hear was the Firth and the flies and bees.

I’d had enough of making the most of it. Getting fresh air. I wanted to crawl to the Co-op, climb into their lolly freezer and slide the hatch closed over my head. I’d cuddle myself in, go crispy like a mammoth, lie there on the ice poles until the bees got bored and the school bell rang and all the weekdays had their names again.

The park got used for drinking now and there were cans all over the grass – black cans, goldish cans, crumpled and stamped-on cans with manly names and stupid wee lightning-bolt logos. Saturday nights I’d hear it all from my room – dafties, running mad on the cider, headlocking one another, tonguing their fed-up lassies in the dark. Even with the duvet pulled right round my lug I couldn’t stop the noise of those Muircross boys.

But it was safer in the daytime, and it was just me and Jo now. I was watching Jo, stood out on the grass kicking blowballs off the dandelions, dog at her feet, arse-revealing hockey shorts on with that big custard-colour trackie top that was her da’s. Two pipe-cleaner legs poking out the bottom, like Big Bird. She must have been baking in that top. Reeking, like me. She had it zipped right the way up to her chin so I knew there were love bites.

That morning Jo and my mam had spoke to each other in that blatant way that told you something was up – they were shite at pretending. How long will you be at the park, Jo? A good few hours at least, Maggie. Excellent, Jo. A lot of sensible nodding, a lot of double-checking the wee unimportant things. I knew there had to be plans because my mam never asked my pals anything. And she never used words like excellent.

I’d kept my mouth shut because it was Sunday and that usually meant a treat. Never a proper present, like trainers or bangles or a belt, but sometimes a Swiss roll, or a heat-up macaroni, or a film out of Blockbuster with crying in it. My mam was in a wheelchair and that made everything a faff , so if she was doing me a treat she would need me out the house – Away and get some fresh air. Stop being fizzy. Away out with Jo.

Jo was twenty. She had curling tongs and she sometimes paid my bus fare, and growing up she’d had tons of boys in her room. She’d found a syringe once and touched it. When her dog had a phantom pregnancy she didn’t cry because she knew that was the circle of life. She’d also got away to college – in Glasgow.

She’d babysat me when I was a wean and she’d had her claws in my mam ever since. The pair of them were always scheming and gossiping, calling me a pee-the-bed, speaking about me like I didn’t exist. My da died when I was four and the boyfriends came and went, and so my mam ended up depending on Jo. Sometimes you knew from Jo’s face that she thought she was better than everyone, but my mam never seemed to see.

I sat back on the bench and thought about treats. What would I want the most right now? I don’t mean skinnier fingers or a fancy house, just something naughty and stupid, like a cone or a cold Lilt. Chips and juice? Or a boy, maybe.

Not for the squeezing, or the love bites, just someone to sit with me on the hot grass and listen. A wee local boy in Nike or Ellesse with an unscarred face and a heart set on skipping this estate and vanishing, like me.

Jo’s dog Bam-Bam waddled over and fl opped down next to a Blackthorn can, panting, eyeing me sidieways from the weeds with that wee bit self-pity and that wee bit suspiciousness that always got me right on edge.

Then Jo came over, fiddling with the leash, and dumped herself down. A minute of heat went by. I couldn’t think of anything else, and Jo loved boasting about boys, so I said it.

‘You got love bites then, Jo?’

‘No,’ she went.

‘Aye you do.’

‘No I don’t!’

‘Zip the trackie top down then.’

She started patting Bam-Bam’s knobbly head and telling her she was good. Bam-Bam was doing her sharky smile, slavering, looking all rascally.

Then Jo went, ‘Fuck off , Cora.’

‘You must be boiling in that top,’ I says. I only had shorts and a T-shirt on.

The park had houses round three sides and then the water. A garden radio was going somewhere. Jo stood up and got Bam-Bam on the leash, ‘Come on. Let’s walk.’

We started across the grass and I put my sunspecs on. They were lime green and creaky and crap and they were free from Boots and I was ten when I got them. It was a beamer to have to wear them.

Jo’s sunspecs were those mad oval white ones with black lenses, like girl singers from the sixties. DKNY on the side, totally smudgeless. Jo was long and thin and bendy with ginger hair in a centre parting. It was chopped straight about chin height and it spread out from her face in two wavy wedges. She always had nice stuff , decent clothes. Jo stood out a mile.

‘Don’t tell me to fuck off , Jo,’ was the first thing I said as we walked.

‘You’re an annoying wee shite. You ask too many questions.’ She said it in that way that made it sound like you couldn’t argue.

We left the park and walked down the steps onto the Causey road. The rubbly ground sloped down then dropped off quick into the Firth. Folk dumped stuff in the layby here and we would sometimes throw it over the low fence and into the water, for a laugh.

Today there were burst-open bin bags and a fake leather armchair. Bam-Bam was jerking Jo forward on the leash and flapping her ham tongue at everything spilling out those bags – onion skins, pill packets, coat hangers, own-brand bean tins. The whole heap was baking in the sun.

Jo tied her up, ‘Let’s chuck that chair.’

We tipped the sweaty chair up easy and fl ung it. It scudded off a rock and seagulls went up and then it bounced down and dropped off the cliff at the bottom, smashing into the waves with a faraway splash.

I wiped my hands on my shorts. ‘So you got a boyfriend now?’

‘No. Why?’ She untied Bam-Bam and held the leash in one hand.

‘The love bites, Jo.’

On her free hand she started nibbling her nails – Purple Crush, again. ‘There’s no love bites.’

‘Zip the top down then.’

‘I don’t want to!’

Jo wasn’t normally shy like this. I’d heard all her Glasgow stories – blue cocktails, night buses, rashes on her arse from the foam parties. Eating fried rice in graveyards with boys. Boys eating her in graveyards. She had so many stories. There had been so many boys.

We started walking. I went, ‘Mind Fozzy? You loved Fozzy.’

She flicked her curls back. ‘Fozzy was good to me.’

‘Fozzy was a creep. He had no lips and his eyes were too close together.’

Jo brought Fozzy to my house once when my mam wasn’t there and it gave me the heebies. He tried to be nice to me but I hated his bony arse being on my settee. I wanted things to go wrong for Fozzy and Jo, and Jo had sensed it, and she got weird with me for ages after. Fozzy did a bolt to Germany last summer and Jo was in bits. I secretly smiled about it probably most days.

‘When you grow up and get a boyfriend then you’ll understand. It’s hard to find a decent boy. Even harder to keep them interested,’ she said.

‘I’d never want a boy like Fozzy.’ I was itching and at my absolute clammiest and I was winding her up on purpose now.

‘Fozzy was from Glasgow. He had a motorbike. You’d be doing well to pull a boy on a pogo stick. Get back to me when you’ve tongued a boy.’

‘Aye, Fozzy had a motorbike but he was probably buying you wee bits of heart-shaped jewellery, wasn’t he? Probably doing smudgy pencil portraits of Bam-Bam? What a beamer.’

She tilted her head down and gawped at me over her sunspecs, ‘Cora Mowat, you’d wash the sugar off a doughnut.’

‘What’s that meant to mean?’

‘That you’re weird and you ruin things.’

‘I’m not weird!’

‘I babysat you for three years. I’ve seen everything in your room. I’ve read your diaries – August 1989, wasn’t it? I want to be a squirrel.’

‘That was a joke, Jo.’

One time I told Jo about the sadness I felt when I saw abandoned microwaves at the side of the road. She was drinking chocolate Yazoo and she laughed so hard she spat it all down her brand-new crop top – she wasn’t even mad about the staining. After that I tried to be careful with what I was letting out in front of her.

The two of us sat down on the bench at the end of the Causey, by the brambles and the bin. If you looked left from here you could see onto our estate – grey boxy-looking houses that zig-zagged down the slope towards the water, jaggy and squashed like pensioner teeth. You could see the gardens that looked over the Firth, including mine, and the rows of low garages we sunbathed on before the tar and the barbed wire went up.

I’d spent almost every minute of my life here, at the edge of Muircross. It was a manky wee hellhole sat out by itself on a lump of coast the shape of a chicken nugget, surrounded by pylons and filled with moonhowlers and old folk and seagulls the size of ironing boards that shat over everything. Chaos and fighting and shite in your fringe, that was Muircross.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Clearing by Katherine May to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.