Why awe matters

Ten ways to coax it back into your life

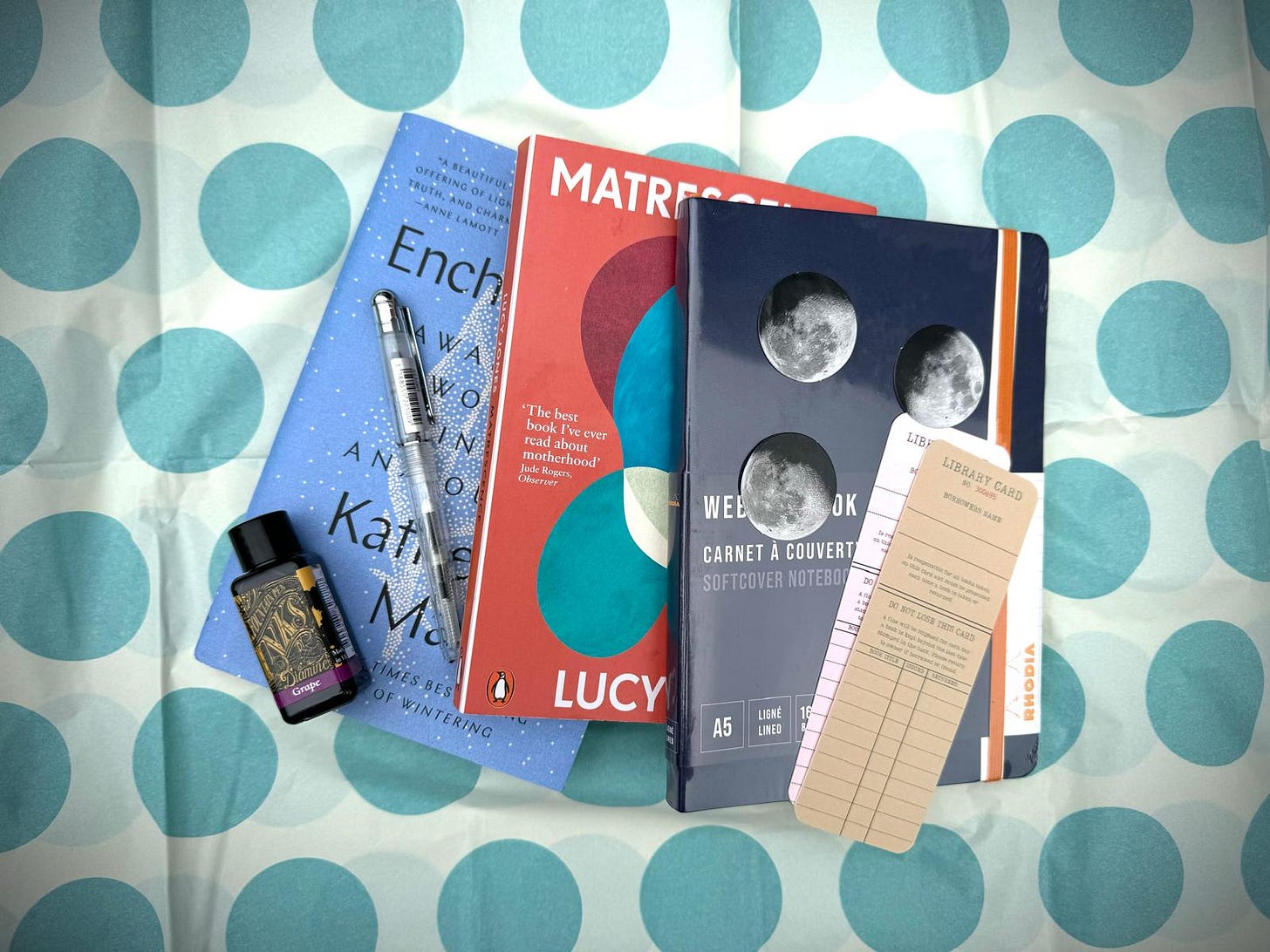

August and September’s Book Club and Creative Questions dates • Win my writing essentials

I spoke last week at the Chautauqua Institution on ‘Why Awe Matters’ - a tricky subject when there are so many terrible things going on in the world. I’m conscious, always, that soft emotions such as awe can seem completely frivolous, and in extremely short supply. For me, that shows exactly how much we need it. We have this instinctive reflex that lets us suddenly understand the context of human life, and it’s there to help us.

But first, a story

When Bert was a baby, he used to get terrible ear infections. They are the family curse; my Dad and I both had exactly the same trouble, and neither of us have the greatest hearing because of it.

One Saturday morning, I noticed the tell-tale signs of one of these infections starting up. Bert was hot and agitated, and I knew I needed to get him to the doctor. Here in the UK, on a weekend, that means calling the dreaded ‘111’ phone line and holding on for hours. Eventually, late into the afternoon, we were allowed to see the duty paediatrician in a surgery in the next town. I waited in the plastic chairs outside with my grizzling baby, and was eventually called in, completely flustered myself. So often in our system, I’ve felt like I have to insist on care, rather than take it for granted that it will flow naturally towards us. I started blurting out the problem, and how often it was occurring, and why it really mattered that the doctor paid attention to us today.

The doctor nodded slowly, and said quietly. ‘We will make everything better. But first, I need to make friends with your son.’

I suddenly realised that this man was far older than any other doctor we’d seen. He turned all of his gentle attention to Bert, and spoke to him, telling him what he needed to do. ‘You and I are going to need to trust each other,’ he said. ‘But we can’t do that without getting to know each other first, huh? May I?’

I passed my little boy over to him, and he cradled him in his arms, talking softly, smiling, telling him about his experience as a doctor and why he could help. Bert immediately relaxed, and smiled. The conversation continued for what felt like an age; there was no rush. Eventually, when the doctor was completely satisfied that a bond had been formed, he looked into Bert’s ears, and wrote a prescription. It was only when we were back out into the street that I realised what I was feeling: a profound sense of awe. Awe at this man’s kindness, his patience, and his depth of experience. Awe that he took the time to form a relationship with an infant, rather than rushing home from his Saturday shift. Awe that he knew exactly how to take care of both of us in that moment.

Well, now I’m crying. And that’s exactly what awe does: it comes at us from strange angles, it’s impossible to command, and it crystallises a moment in a way that stays with us forever.

What is awe?

Awe isn’t necessarily nice; it’s not the same as pretty, or grand. It contains within it a component of darkness, perhaps a sense that we might be overcome by what we’re witnessing, or perhaps a feeling that we have been brought closer, somehow, to the mechanics of the universe. Awe is life or death. Awe is not Instagrammable, despite what we tend to believe.

I’ve been calling awe an emotion, but that doesn’t quite nail it. Awe is notoriously hard to define. It’s better described as a life-shifting experience, or an intensely present state of being. An experience of awe might contain:

A sense of vastness, or ineffable power.

A connection to greatness.

A feeling of heightened reality.

An experience of flow, or being in the moment - nothing else matters at that time.

An immersion in beauty.

A profound emotional connection to the moment that’s unfolding before you.

Most importantly, awe should make us feel small, whether that’s in time, in physical space, or in the presence of a greater mind or consciousness. When I spoke to Dacher Keltner about it on my podcast, he talked about a shift occurring: awe makes us realise how small we are in the broader context of the universe. This change in perspective is a mixture of fear and delight; it leaves us with an increased sense of humility, and perhaps even a greater sense of purpose, or a calling. ‘Big awe’ moments are life-changing, once-in-a-lifetime experiences.

This is all beginning to sound a bit inaccessible to me…

…or that’s what I thought when I started to research awe for my book, Enchantment. At this point in history, awe has become an experience we attempt to buy in a holiday of a lifetime to a far-off, expensive place. Even if we can do this, awe can be elusive; it does not obey our command.

And where does that leave those of us who are stuck at home, perhaps in caring roles, or restricted by disability or illness - or just not very rich? Those are all quite ordinary ways of living, and it troubled me, as I sat down to write, that the current wisdom on awe excludes all these people. It didn’t seem fair, but it didn’t seem true, either, on an evolutionary scale. If humans are primed to feel this radical shift in perspective, then we can assume that it’s beneficial to us, an adaptation. Why, then, should only some people have access to it?

Therefore, I started to explore the idea of ‘small awe’ or ‘enchantment’ as I call it - the micro experiences of awe that can be embedded in the everyday. These are the opposite of those big, surprising events that knock the breath from our lungs. Enchantment is a commitment to practising awe, to committing our attention to the world around us, and learning to feel its tingle of magic. It’s about choosing engagement over numbness and distraction, finding ways to engage and connect. In many ways, it’s about returning to a childlike state when anything in our vicinity could set off waves of fascination. It’s an act of unlearning, of unforgetting.

I believe it’s possible to find awe in so many things around us: the vast age of pebbles on the ground, the way that plants grow from air and water, the moon in the sky at night, the way that children grow, the sheer volume of seas and rivers, the talent, invention, and wisdom we witness in other people every single day (from watching sport on TV to reading a novel), the shape of the landscapes around us, still visible under all the buildings we’ve put on top of it; the life that exists in those buildings. Once you start looking, it’s everywhere.

Why does this ‘small awe’ matter?

Let me list the ways:

It comforts and soothes us in difficult times, and therefore helps us to rest and reset, so that we can go back out into the world renewed.

It opens up reflective space in which we can think about the larger forces that govern us and the bigger themes in our lives.

It therefore helps to protect against burnout, and to notice early when we’re knocking on the door of exhaustion.

It reconnects us to our sense of purpose, to our ethical imperative. It can set us on a new and better path.

It allows us to sense the changes that are already waiting to happen.

It takes us back into our bodies, and engages our multiple senses again.

It encourages connective thinking, the joining together of disparate ideas - and it often leaves us craving more knowledge.

By shifting our perspective, it makes us feel more connected to the rest of humanity again. It draws out our compassion and empathy.

It is contagious: we can’t help but talk about it, and we can feel each other’s awe.

Feeling awe cracks us open. It is a vulnerable experience; it softens us in a time when it’s so easy to harden.

It’s a muscle. The more we practise, the more receptive we are to everyday awe, and the more ready we will be for that next hit of big awe.

Awe is not a silly, nice-to-have frippery; it’s not a distraction from more important events. It is not something that should rightly be dispensed-of by more serious minds. This is a need we hold within us, an artefact of our survival. It’s something that we should re-train in ourselves, so that we can pass it on.

Ten ways to rediscover awe

Go back to your childhood fascinations.

What did you love to do as a child, which you lost in the rush to grow up? Go back to those things, whether it’s collecting pebbles in our pocket, hanging out with snails, or swinging high on a swing. There are clues here to your personal sense of wonder.

Make contact with the outside every day.

Even if you just open a window and breathe the air for a minute, or step outside your front door, it’s a process of reconnecting. If you have more time and energy, go for a walk. Notice what attracts your attention. Let yourself be drawn towards those things.

Have patience.

The signals of our enchantment can be very faint at first. Sometimes we’re out of the habit, and sometimes we’ve shut down our senses in order to cope with a hostile environment. Be kind to yourself, and don’t expect big blasts of cosmic amazement right away. All you need to do is to keep coming back, and noticing.

Foster curiosity.

So many of us switch off our curiosity as we grow up - we feel that we have to already know everything. Head off in the opposite direction. Notice what you don’t know. Discover what piques your interest. Ask too many questions, all the time. Follow your own leads.

Build knowledge.

Wonder isn’t the opposite of knowledge - they’re deeply entwined. Building knowledge around the object of your fascination (and that includes spending time going down internet rabbit holes) deepens your sense of awe. It’s a call and response. Lean into it.

Go on adventures.

One of the things I’ve learned to do in my life is to go and see the things that interest me. If I can get the train there, or drive, I go. It doesn’t have to be far or expensive; most of my adventures happen very close to home. So for example, I’ll see a landscape feature on a map and go and see what it looks like; or I’ll go on a day trip to see a monument that’s always called to me. Don’t wait for permission; just go. You’re allowed.

Listen to other people’s wonder.

Awe speaks to awe. Listen carefully when people tell you what they love, and share your own fascinations. Pay particular attention to stories of awe. Notice the complexity of these accounts - they often take place at life’s darkest moments. This is an exercise in openness and connection, but it will teach you all the astonishing different forms that awe can take.

Write it down.

I guess I would think this wouldn’t I, but writing about your feelings of awe, however small, can really help to explore and develop your experiences. Don’t set any rules - you don’t have to write to a schedule, or create beautiful prose - just log what you saw. ‘Today I watched a flock of birds all flying together…’

Learn your lore.

What is the folklore of where you live? What are the mythologies held in your family or social group? I tend to think that these kinds of stories - even if we no longer believe in them - point us to seeing life on a grander scale. They encourage us to look at our landscapes in a new light, and to think about human emotions as timeless. They actually serve to deepen our connection with everyday life.

Don’t be afraid to pause.

One of the key barriers to enchantment is our unwillingness to pause, just for a moment. We tend to move at speed through our lives, counting off steps taken and calories burned. That means that stopping is a kind of failure; it disrupts our measurable achievements. Have you ever gone on a walk with a toddler? They endlessly stop to look at things. We need to re-learn that skill. Let your attention catch on the world around you, and stop to take a closer look. Meander like a river through your world. You won’t regret it.

I hope that’s been a useful guide! If you’ve had an experience of awe - big or small - I’d love to read about it in the comments!

Take care,

Katherine

Win my writing essentials!

Take out an annual subscription this month - or renew an existing one - and you’ll be entered into a prize draw to win a very special box of my my writing essentials. This contains all the items I rely on for my daily writing practice, including a Rhodia notebook, stickers to decorate it, a Herbin refillable ink pen, Diamine ink, bookmarks and blackwing pencils. There’s also a signed copy of Enchantment (and a signed bookplate to stick into your existing copy) and a paperback of this month’s Book Club pick, Matrescence by Lucy Jones.

To enter into the prize draw, just take out an annual subscription to The Clearing, or renew your existing subscription - we’ll gather the names together and draw a winner after 31st August. The winner will be contacted by email.

Good luck! And thanks for subscribing :)

Live subscriber events:

If you think a friend or loved one would enjoy The Clearing by Katherine May, gift subscriptions are available here | Website | Buy: Enchantment UK /US | Buy: Wintering UK / US | Buy: The Electricity of Every Living Thing UK / US

This newsletter may contain affiliate links.

This is wonderful, thank you! I’ve found the great poet Mary Oliver to be such a fantastic ‘teacher’ on awe in the everyday. As she says in her poem ‘Sometimes’:

“Instructions for living a life:

Pay attention.

Be astonished.

Tell about it.”

❤️🔥

My first memory of awe was an occasion at school when I was learning to write. I had copied a sentence from the blackboard and the teacher suggested we might like to continue with another sentence 'of our own'. The idea seemed monumental - like throwing myself off a cliff, but after a while I tried it. And there, on the paper, something that I thought in my head - came out at the end of my pencil. My breath stopped in the wonder of it. I will never get over it.