As a child, I found the world intrinsically magical. Not all of the magic was good; I was convinced that a ghost lived in the cupboard in my bedroom, and that it was moving my stuff around while I slept (I was disabused of this notion one night when I woke mid-sleepwalk to find myself burying my coin purse in a box of cornflakes, but maybe that’s a story for another time). Nor was I interested in the Disney version of magic, the kind that spewed galaxies of twinkling stars from the wands of fairy godmothers. My magic was never so twee. But I did feel as though certain things - certain stories, certain tricks of the light, the way that the moon chased me home or sea roared through the conch shell in my grandparents’ bathroom - carried a charge, a magnetism, a sense that world contained a wellspring of power that I could intercept, sometimes, in the right state of mind.

I grew up to reject every shred of it. If you’d have met me in my twenties, you’d have found me robustly, argumentatively, trying to demonstrate my absolute rationality. It seemed clear to me that my purpose in life was to reject any shred of magical thinking, and to roundly mock anyone who thought differently. It was the age of Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins, of the Nine Lessons and Carols for Godless People, and I wanted in.

There were a few problems though, which became more and more obvious to me as the decade wore on. First and foremost, the self-proclaimed leaders of this movement didn’t seem to be terribly appealing people, displaying some surprisingly unempirical sexist views, and a marked tendency to slip into Islamophobia. Their angry secularism didn’t seem to make them particularly happy. Meanwhile, the ‘spiritual’ people I knew seemed more content, and also more open-minded. It was not enough to convert me, but did find it confusing. How could I, who was so carefully Right About Everything, not have the upper hand here?

In fact, I was luridly unhappy most of the time, filled with self-loathing and fury at my human ineptitude, so anxious that I couldn’t breathe. When I look back at my former self, I don’t think this was caused by my rationalist beliefs, but I do see that I pushed away anything that might have offered me connection and comfort, or opened up a space for reflection. I had no model of placing myself within the world that didn’t position me as a lone individual, either striving upwards or failing. Given that I mostly experienced the latter, I felt I had no value. I had no other way of thinking about it, no community to urge me into gentler ways of seeing myself. I would have struggled to admit it at the time, but I was lonely, and lost, and desolate. I needed something more, but I couldn’t begin to ask for it.

Most of all, though, it always felt like an enormous effort to repress my sense of magic. My belief in a cold, meaningless universe didn’t come naturally. For all the evidence I saw, all the data I collected, I couldn’t help but feel that there was something more to life than the demonstrable facts. I still felt the people were connected in ways that were not fully explained in my own philosophy, that there was a call and response between my body and the earth that held it, that a discreet and fluid intelligence bound everything together. It never made sense to me to try to explain it, and I don’t think it ever will. I am constitutionally ill-suited to pinning it down.

‘Magic’ is probably a strange word to use for what I’m trying to explain, but then ‘God’ carries a lot of baggage, or at least it always has for me. Eventually, my defences broke down, but not in any sensible kind of order. My behaviour changed before my opinions caught up. I found that I was praying without thinking that there was any being to pray to. For a while, I was forever picking up spiritual texts in charity shops, just out of a sense of intellectual curiosity, you understand, and not out of any personal seeking. It would have been lax, wouldn’t it, not to read all the foundational texts of the yoga classes I so adored? How could I enjoy haiku without reading up on Zen? Can you claim to truly love Ursula Le Guin without reading the Tao Te Ching? A Nick Cave lyric lodged itself in my mind: I don’t believe in an interventionist God. It was curious, that specific insertion of ‘interventionist’. Apparently that was not a requirement in the first place. My concept of God started to disintegrate.

One morning, sitting in a traffic jam with my closest friend, both of us hungover from one of our habitually heavy weekends, I became aware of a thread in all of our conversations through the years. It arrived gently in my being as if it had always been there, this understanding of a subtext in all our conversations about the inanity of religion, our clever, brilliant, superior atheism.

‘I think you believe in God, don’t you?’ I said.

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘I think I do.’

‘I thought so. Me too.’

We left it at that. There was no more to be said, or at least nothing that either of us could have understood.

I still don’t practise any religion. I still believe in science. Having researched a good part of a doctorate in the evolutionary theory of narrative, I spend a surprising amount of time correcting fellow rationalists on their feeble grasp of Darwinism. Believing in God did not turn out to be the slippery slope I feared. But then, the kind of God I believe in is pretty hard to pin down. When I try to explain what I think - what I sense - the whole thing tends to unravel. The best stab I ever make of it is to say that my God is the sum total of all consciousness. It might just be a construct, a concept, and I’m fine with that. The more I think about humanity as a whole, as a one, the more I notice how good we are, on average. That noticing alone weaves its own kind of magic. No supernatural beliefs are required.

What seems irrational to me, now, is to argue against the observation of my own senses. That does not mean that I want to convert anyone to my way of seeing things - far from it. In fact, I strongly suspect that we all perceive things differently, and that we all have different desires. That strikes me as… a good thing? I recently read a proof of Elizabeth Oldfield’s Fully Alive (out in May) and I noticed that she finds ecstatic experience in groups; for me, ecstasy only comes in solitude. I’ve never felt a calling towards her Christian faith, but I loved being able to understand her experience and interpretation of the scriptures. My husband, meanwhile, senses nothing remotely magical in the world, and is honestly pretty content. He does not need what I need. Similarly, I could live without the overflowing collection of funk records in which he finds transcendence, but I also like having them around. Each to their own doesn’t have to mean separation.

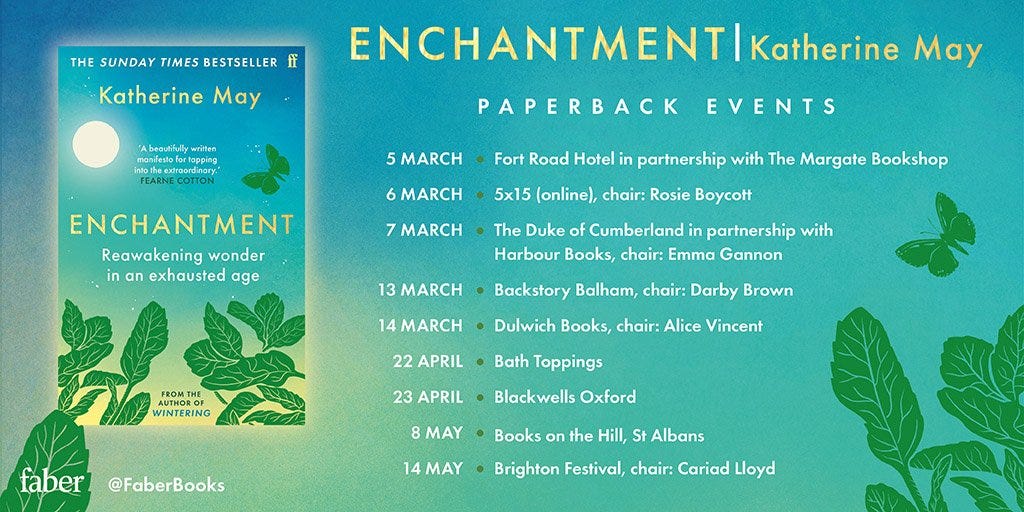

Why am I writing all this? Well, it’s a year since Enchantment came out, and while I’ve been promoting the UK paperback, the thought that came up over and over again was: I can’t believe you wrote this. In this time when the world seems drained of any sense of magic - when, in fact, so much feels cruel and apocalyptic and grim - it seems a bit ridiculous to publish a book about finding the world beautiful and brimming with wonder. My own inner critic (who is myself aged 27, high on incomprehensible literary fiction and ideological purity) was mortified on my behalf.

But the problem is, I think it’s absolutely necessary. Just as everything seems so desolate, when we feel so isolated and afraid, confused and exhausted, when anger threatens to taint our entire social order, many of us are yearning for something that connects us again, that draws us back into our bodies, and tethers us to our landscapes. Something that gives us back our delight, and allows us to explore our longings. When so many of us are losing hope, it seems vital that we renew our connection to a world that’s worth saving; that we show a more meaningful way to live than hate and individualism. We have seen the harm that comes when we all harden. It’s time to learn how to soften into this strange, conflicted era.

The trick, I think, is not to seek belief, but contact. And that contact is intensely personal. It cannot be handed to you by someone else. It is, at best, a lifelong pursuit. That’s what I wrote a book about.

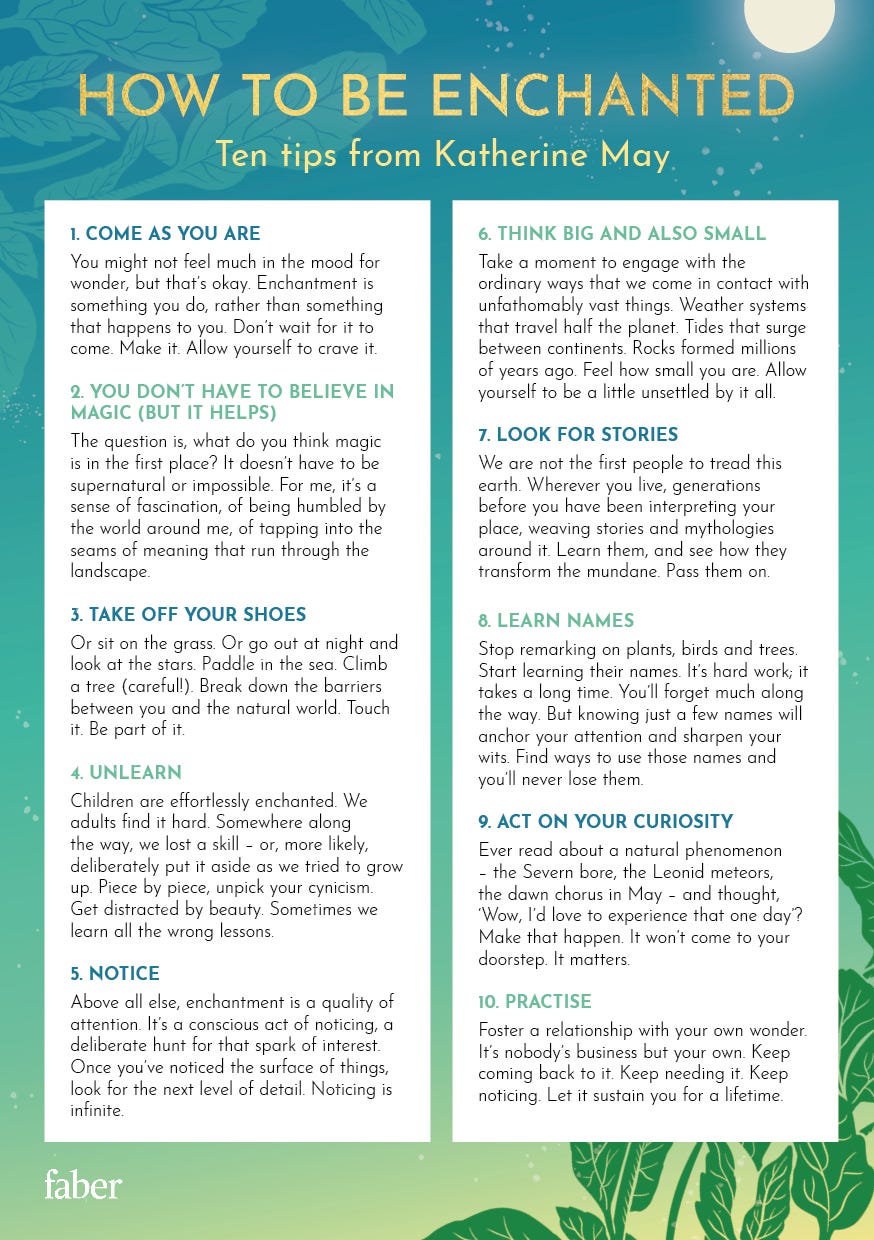

My publishers at Faber have put together some beautiful posters for UK libraries, featuring ten ideas for finding your own sense of enchantment. I thought I’d share them with you here, just in case you want to begin.

(For people using screen readers, the full text is at the bottom of the page.)

Take care,

Katherine

HOW TO BE ENCHANTED

Come as you are.

You might not feel much in the mood for wonder, but that’s okay. Enchantment is something you do, rather than something that happens to you. Don’t wait for it to come. Make it. Allow yourself to crave it.

You don’t have to believe in magic (but it helps).

The question is, what do you think magic is in the first place? It doesn’t have to be supernatural or impossible. For me, it’s a sense of fascination, of being humbled by the world around me, of tapping into the seams of meaning that run through the landscape.

Take off your shoes.

Or sit on the grass. Or go out at night and look at the stars. Paddle in the sea. Climb a tree (careful!). Break down the barriers between you and the natural world. Touch it. Be part of it.

Unlearn.

Children are effortlessly enchanted. We adults find it hard. Somewhere along the way, we lost a skill - or, more likely, deliberately put it aside as we tried to grow up. Piece by piece, unpick your cynicism. Get distracted by beauty. Sometimes we learn all the wrong lessons.

Notice.

Above all else, enchantment is a quality of attention. It’s a conscious act of noticing, a deliberate hunt for that spark of interest. Once you’ve noticed the surface of things, look for the next level of detail. Noticing is infinite.

Think big. And also small.

Take a moment to engage with the ordinary ways that we come in contact with unfathomably vast things. Weather systems that travel half the planet. Tides that surge between continents. Rocks formed millions of years ago. Feel how small you are. Allow yourself to be a little unsettled by it all.

Look for stories.

We are not the first people to tread this earth. Wherever you live, generations before you have been interpreting your place, weaving stories and mythologies around it. Learn them, and see how they transform the mundane. Pass them on.

Learn names.

Stop remarking on plants, birds and trees. Start learning their names. It’s hard work; it takes a long time. You’ll forget much along the way. But knowing just a few names will anchor your attention and sharpen your wits. Find ways to use those names and you’ll never lose them.

Act on your curiosity.

Ever read about a natural phenomenon - the Severn bore, the Leonid meteors, the dawn chorus in May - and thought, ‘Wow, I’d love to experience that one day.’ Make that happen. It won’t come to your doorstep. It matters.

Practise.

Foster a relationship with your own wonder. It’s nobody’s business but your own. Keep coming back to it. Keep needing it. Keep noticing. Let it sustain you for a lifetime.

If you think a friend or loved one would enjoy The Clearing by Katherine May, gift subscriptions are available here | Website | Buy: Enchantment UK /US | Buy: Wintering UK / US | Buy: The Electricity of Every Living Thing UK / US

This newsletter may contain affiliate links.

"Many of us are yearning for something that connects us again, that draws us back into our bodies, and tethers us to our landscapes. Something that gives us back our delight, and allows us to explore our longings." Such a beautifully balanced essay, Katherine, which sets out your views so honestly and clearly while allowing space for others with different views or beliefs to think along with you.

Enchantment is an absolutely necessary book, Katherine. We need connection, ritual, and yes, magic more than ever. You’ve vocalised things I’ve been feeling for a while and I’ve been recommending your book to so many fellow travellers. Thank you.